My Story

Why I code

The pre-coding years

Throughout my teenage years, I'd been very into video games, so it seemed logical that when it came to choosing my subjects for sixth-form college, that computing was one of them.

On the first day of this A-level computing course, aged 16, I sat in the classroom, listening to the teacher drone on in his monotone voice about topics that I didn't understand. I looked around the class, and saw myself surrounded by peers that I couldn't relate to.

I felt very out of place.

I had some friends who'd taken economics and business studies, and they were raving about how fun the content had been of their first class, and how charismatic their teacher was. They had genuinely enjoyed it.

Having felt like an imposter, I quickly changed courses and dropped computing in favour of studying economics and business. And you know what?

My friends were right.

I wasn't even in their class. I had different peers and a different teacher. But the way the course was taught was fun and exciting. It felt like real world knowledge that would be valuable.

The way I saw the world at this point, was that I'd been in education for about as long as I had memories.

The furthest I'd ventured from my hometown of London, was that I'd gone on a school trip to Berlin when I was 14, although like with all school trips, it wasn't like I had the freedom to roam the city alone.

Having never travelled further than that, on finishing sixth-form college at 17, the world seemed a very big place to me, ripe for exploring.

There had to be more to life than just sitting in classrooms. And so rather than going straight off to university like everyone I knew, I decided to take a gap year.

My plan was simple. I was going to work for the first 6 months of this gap year and save every penny that I could. Then with the money that I'd saved, I was going to go overseas for the 6 months afterwards, and travel to... wherever.

So I trained to be a lifeguard, and I got a job at my local swimming pool. And you know the great thing about being a lifeguard?

You just sit there all day and look at water.

Although it might not be the most engaging work, it isn't stressful, and it isn't physcially challenging.

Of the jobs I'd had in my life up to this point, the first was that I'd delivered newspapers for a couple of years from 13. That work's not bad for a 13 year old, but it's not that easy either. Dragging around a cart with hundreds of papers in it will wear you out.

Then I'd worked in a restaurant kitchen for a few months, before moving to a pub and working front-of-house. All of these jobs were either stressful or demanding in some way, so the amount you could do them was finite.

Working as a lifeguard, I got to just sit there and look at water, lost in my own thoughts. And with a job like that, you can do it pretty indefinitely without getting stressed or tired.

Sure, there are moments when you start thinking to yourself that you'd rather be anywhere else, but I think that's going to be the case with anything you do too much.

What this meant though, was that I took every hour of overtime that became available. I would work 90+ hours some weeks, staring at water.

The pool would open at 6am, I was there. It would close at 10:30pm, I was there. Then I'd be back again at 6am the next morning to do it all again.

I was on little more than minimum wage. But even on minimum wage, if you work enough, you can make a decent amount of money. Especially for an 18 year old.

I'd never had much money before, and now suddenly I was looking at my bank balance each month being all... "Ka-ching!"

When you suddenly find yourself living a very lucrative lifestyle, it's hard to turn your back on it to go travelling.

So I ended up working my entire gap year, and arrived at university with a bank balance that would have made most of my peers envious.

Back in my formative years, I'd always fared well at school. I consistently got A grades, and had I kept on that path, really could have gone onto the best universities if I'd wanted to.

Unfortunately I hit a bit of a rebellious patch in my teens, and at that moment, education didn't seem all that important.

In fact, for those few years, I was more or less determined to do the opposite of anything I'd ever been told to do.

No more homework, that just gets in the way of playing video games. No more exercise. No more healthy food.

I arrived in my teenage years a fit and healthy straight-A student. By 18 I was overweight, unfit, and it was only thanks to the knowledge I'd procured prior to my teens, that I was able to get the grades to go to university at all. Oxford and Cambridge weren't going to be in my future though.

The advantage that I had over most other university applicants, was that by taking a gap year, I already knew my grades.

At that time you could apply to six universities, and the way I looked at it, was that having my grades already, if I applied for any university of which I had the required grades, I was going to get in. So why not apply for three universities of which I know I'll get in, and then I can apply for three long-shot universities that I don't quite have the grades for, because... well you miss 100% of the shots you don't take.

I still favoured business over any other subject, so I was looking for a university with a good business school.

I'd now had a taste of what it was like to have money, and I liked it. And seeing as I was good at and enjoyed studying business, taking it at university just made sense.

More important in my decision process, was I only considered courses that offered a year on exchange.

I might have foregone the intended six months of travel during my gap year, but it hadn't ever left my mind, and if I could travel as part of my studies then... well why not?

Two of my three long-shot universities rejected me.

Liverpool University said no. Oxford Brookes University said no. So I went to the third one.

Glamorous, alluring and seductive. All words you're not going to associate with going to university in Hull, at that time considered the UK's worst city, as many people insisted on telling me.

But I'll tell you something, it isn't half a good place to go to university.

My rent was a third less than people I knew studying in nearby York and Leeds, and there wasn't a night in Hull where you couldn't find a bar doing £1 drinks.

I know that every university has a party culture, but in Hull it was a bit different.

You have to have a slightly sadomasochistic personality to ever go to Hull anyway. And when you mesh those personalities with the cheaper drinks and the cheaper living costs, it made for a very fun time.

I visitied friends at other universities. It was never quite the same as in Hull.

I'd got over my teenage rebellious phase during my gap year, and conscious of how out of shape I'd become, had slimmed down to, judging by photos from then, concerningly thin levels.

Through a combination of running and starvation, I shed almost half my bodyweight in just a few weeks.

Looking back, that might not have been the healthiest way to do it, but it was effective.

Fitness, and running in particular, were suddenly very important to me.

I'd gone to university with a very open mind. This was my first time living away from home, and I was determined to try new things.

It seemed an obvious choice therefore, that I'd join the university running club, but when I met with them... well they're very uninspiring people.

Instead I joined the American football club.

Had I ever seen a game of American football before?

No.

Did I know what it was, or how to play?

No.

Was I, now weighing less than 60kgs, the right size and physique to play American football?

No.

It was one of those decisions, where looking back, I don't know what went through my mind to make me think it was a good idea. But I stuck with it through the duration of my studies, and loved every second.

No aspect of university life influenced me more than being on that team. And I was committed to it.

12 months earlier I'd been horrendously out of shape. Now I was worryingly skinny. All of a sudden I found myself with the motivation to bulk-up, which really introduced a gym lifestyle to me.

For my entire university life, I lived in the gym. I was there almost everyday.

I ate well, but I ate a lot in order to gain weight.

As well as the gym, I kept up with running, and I had American football practice twice a week. And burning all those calories, eating sufficiently to gain weight wasn't even that easy.

Try telling that to the guy who, 12 months earlier, was fat and getting tired walking up a flight of stairs.

Fitness now took precedence over everything in my life, even my studies.

Although I hadn't travelled during my gap year, I had promised myself that during the summer break after my first year at uni, I'd travel then instead.

That was four months to go abroad, and what I'd done was get a Canadian working visa. And no sooner had the final exams for the first year ended, I was on a flight to Vancouver; my first time leaving western Europe.

This was my first time, going somewhere new and unfamiliar, and having to build a life for myself there, even if it was just for the short-term.

I had my first night in a hostel booked, but after that I was on my own.

I quickly found myself a flat-share, and I got a part-time job bussing tables in a bar, and another one working for a waiting agency.

Neither the most glamorous job in the world, but they paid the bills.

One night, the waiting agency send me to an event at the Vancouver Aquarium. A wedding. It was a great place for a wedding actually. The dinner took place underneath one of the tanks, so you ate dinner with all these animals swimming over your head.

The best part for me though, was that after the party had finished and everything was cleared away, I got to wander around this aquarium in the middle of the night, watching all the animals sleeping.

That was where I discovered that otters sleep holding hands.

Vancouver was an amazing city to go to. This was my first time ever travelling, or even going on holiday on my own. And it was a great place for it to all begin.

It's a city with the sea on one side, and mountains on the other. Nowhere in Vancouver do you not get stunning views. And to this day, I feel a great level of affection towards it.

But one thing I'd done, was that when I'd booked my flights, I'd flown out of London to Vancouver. However, my flight back to London four months later, that left from New York. And if you look at a map, Vancouver and New York aren't exactly next to each other. I'd set it up so that I had to do some travelling before I got home again, so after about 10 weeks, I packed-up and I left Vancouver.

This part, you could perhaps say, was my introduction to backpacking.

I initially headed over to Vancouver Island, before spending two days on ferries going up through some stunning coastline until I found myself in Alaska.

I might have matured slightly from the rebellious teenager playing video games, but I was still only 19, and I hadn't exactly learned to be mindful of my safety, wandering up mountains in shorts and a t-shirt, no map, no clue where I was going.

As I learned the hard way, snow melts from the bottom as much as it does from the top, so if you happen to fall through it, it's not like the ground's right underneath. And now was late summer, so when I did find myself on snow, up a mountain by myself in a t-shirt and shorts, I was lucky I wasn't injured when it gave way beneath me.

But you learn by making mistakes, and so long as those mistakes don't kill you, you know better for next time.

Of these six weeks before I got to New York, about one full week was spent in transit.

24 hours on a bus one day. 28 hours a couple of days later. It was 52 hours sitting on a bus before I'd made my way east, but my logic had been that you don't see anything while sitting on a plane, and so I'd gone from Alaska to New York by bus, stopping for a couple of days in various towns and cities as I went.

And you know what?

52 hours sitting on a bus might not sound everyone's cup of tea, but I loved every second of it.

This trip had introduced me to travelling, and it was fair to say that I'd caught the bug.

Luckily I had a year on exchange to look forward to as the third year of my degree. And although my first choice had been to go to Copenhagen Business School, I was given my second choice: Dalhousie University, back in Canada again, although this time on the east coast.

It was a new university to me, in another country. All the international students went through inductions together, so we all got to know each other. People from the US, Australia and New Zealand, Mexico, Korea, all over Europe...

They were some fun parties too.

Having never spent more than a few days overseas a couple of years before this, I'd now spent more than a year away in these two trips.

And having arrived at university with a love of money and a desire to be rich, that no longer seemed so important to me.

The world's too big and life too short to spend it sitting in an office, just to make money.

For the value of having a degree, I finished my final year of university. But in truth, I knew by now that I was never going to make use of this business degree.

If I'd followed the typical career path of a business graduate, I'd have found myself a low-level management job in some office on graduating, and spent the next forty years of my life saving a pension and paying-off a mortgage and having 2.4 children and... I just couldn't face it.

Nothing in life scares me more than regret. Even back then, I always imagined that one day, I was going to find myself, lying on my death bed, looking back over my life, too late to change anything or do anything new. And in that moment, I don't want to find myself looking back with regret.

And if I'd followed the path laid-out for me here; the path of a business graduate, to spend his life working in an office, there's no way I wouldn't look back with regret.

My first time abroad had given me the travel bug. This year on exchange had done nothing to deter me. And so by now, I knew that I was going to graduate, and I was going to leave.

I needed to live my life.

Being just an ocean away, and being able to get one more working visa there, I started this post-graduation trip back in Canada.

Before leaving, I got a job as a lifty at a ski resort.

To get that job, you had to be able to ski. I couldn't ski. So I did what anyone would do in that situation.

I lied.

I figured I'd be able to pick it up quickly enough.

The alternative was working some job in the resort; cleaning rooms or serving people in a restaurant.

I wasn't working at a mountain to spend all day at the bottom of it.

Working as a lifty, February 2009

Working as a lifty, February 2009

It made the first couple of weeks of this job a bit awkward as I tried my best to pretend that I could ski, when actually I was terrified of anything but the flattest runs. But after a couple of weeks, I got really comfortable on my skis, and a couple of weeks after that, I was flying down this mountain.

Until I wasn't.

While skiing too fast, I overshot a turn. I leaned-into it to try and compensate, and my skis went out from under me, and I started tumbling.

My right ski detached itself from my boot, my left ski didn't. I was tumbling, but with my ski still attached, my left leg couldn't follow me.

In all this commotion, to this day I can vividly recall the feeling that my left femur was about to snap in half. Bearing that in mind, I consider myself lucky that I survived this fall with nothing more than cartilage damage. However, apart from some fairly flat runs in early spring, it put an end to my ski season, and it's an injury I still deal with to this day.

That sucks, but as with anything, you can't go back in time an change what happened, all you can do is learn from it. And this was perhaps the moment, now 23, that I learned that I wasn't invincible.

I'd played American football weighing less than 60kgs, and didn't care if I got hurt. I'd climbed mountains in Alaska without even a map. I just had absolute faith in myself to not die. All of a sudden though, I showed myself to be human. And while having pain in my knee to this day is an inconvenience, I always take it as a reminder that... hey, you've only got one body. Treat it well.

This ski season had lasted for about 5 months, but I was in Canada on a 12 month visa, and my plan was to head back to Vancouver, and to find some work there. What ended up happening though, was I learned about WWOOFing. WWOOF, standing for 'World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms.'

The 'farms' in there is a bit deceptive, because it's open to anyone with an outdoors area that wants some free labour.

But the agreement is that you go to a "farm", and in exchange for food and board, you work for around 5 hours per day, 5 days per week.

That might sound like slave labour on the surface, but for someone in my situation, it was great.

Like I said, it wasn't limited to farms, and in my first WWOOFing spot I worked on an independent resort on this barely populated island in the Gulf Islands between Vancouver Island and mainland Canada.

I'd been planning on going there for a week or two. I ended up staying for eight. When the resort wasn't full, I got to stay in the private cabins. These cost in excess of $300 to rent for a night. When there were events, such as weddings, there was an on site professional chef who would cook me dinner, otherwise I got free-reign to use this industrial kitchen. And the island itself was beautiful. You could run for miles and not see another person, and the beaches were glorious.

All that in exchange for 5 hours of gardening per day? Yes please.

It might not have felt like it as I ate my professionally-cooked meals, while sleeping in my $300 rooms, but I was very much in backpacker mode by now.

I was fully aware that the sooner the money in my bank account dried-up, the sooner I'd have to stop and settle down somewhere again. Every penny that I could save, I saved.

I continued WWOOFing in several more spots. And as I travelled around, I did so by thumb.

I'd bought myself a tent that I carried around in my backpack. That was my safety net, because when you're hitchhiking, you never quite know how far you can make it in a day or where you're going to get dropped off.

I spent many nights camped at the side of the road.

Home for the night, August 2009

Home for the night, August 2009

But that, for my remaining months in Canada, became my life.

I remember well the first time I hitchhiked. I'd met some hippies at my first WWOOFing gig who'd told me how easy it was, and I do remember that first time, standing at the side of the road with my thumb in the air, thinking "I look like such an idiot."

But after not too long, this girl picked me up. She drove me for a while until we parted ways, and I started again. It always astounded me how willing people were to let a stranger into their car, but I could get further in a day hitchhiking than I could by bus.

Often people wanted the company. Truckers especially, wanted someone to talk to. At one point I was picked up by this Romanian couple who worked in Vancouver. They'd decided to go on a road trip together, but it wasn't going very well, so they picked me up so they didn't have to talk to each other.

I stayed with them for three days on my way to Dawson City in the north of the country.

There was a road in Northern Canada famed for hitchhikers getting murdered. I didn't know that until I was already halfway along it, but I never met anyone who struck me as a serial killer. It was generally a lot of fun, and for the people you met, much better than taking the bus.

I made it up to Dawson City, and then back down again. I made it all the way over to the east of the country, finding myself in little towns that didn't even have buses running to them on the way.

If you don't mind the whole murdering hitchhikers thing, it's a great way to travel.

But alas, all good things must come to an end, and my 12 month visa in Canada was nearing its expiration.

Now this was not the end. It was not even the beginning of the end. But it was, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

When I'd left England 12 months earlier, I'd said to myself and to others, that this was going to be a 10 year trip. Canada was to be my first, but certainly not my last stop.

The wonderful thing about Canada, or one of the wonderful things about Canada, is how sparsely populated it is.

I'm sure that it's changed now, but I remember a stat for The Yukon in Northern Canada at that time, where it had a population of 34,000 people. However, 26,000 of them were in Whitehorse, the provincial capital.

A total of 8,000 people populated the rest of this province, that is two-and-a-half times the size of the UK.

You can understand a bit more from that, why hitch-hiking around there is so easy.

You might only see one car every few minutes, but the frequency with which they pick you up is so great, because who wants to drive for hundreds of miles alone?

I remember seeing a sign warning that the next gas station was 1,000 miles away.

I was about to head south into the US, where my feeling was that things were going to be a bit different.

Not only is the US a lot more populated than its northern neighbour, but hitchiking isn't even legal in all states.

Almost everyone in the US has a car. And for the few who don't, if you want to travel, you take the Greyhound bus. And at this time, Greyhound offered a 'Freedom Pass', where for $500, you could take unlimited buses for two months.

My thinking was that if I slept on enough buses, that pass would pay for itself in money I saved on accommodation.

And so that was how my time in the US was. I didn't sleep on Greyhound buses every night, that would be enough to drive anyone crazy. But anytime I was travelling somewhere, I made sure to do so at night-time. And if I was in a town and couldn't find somewhere to stay within my very restrictive budget, I'd go to the bus station in the evening and take a bus anywhere 10-12 hours away.

Much like hitchhiking in Canada, I met some very interesting people on those buses.

I learned that in the US, when someone gets released from prison, they give them a Greyhound bus ticket to get home again. There was one point where five of us were standing around chatting at a rest-stop, and I was the only one there that didn't have prison stories to share.

Also like hitchhiking in Canada, this way of travelling took me to some great places that I probably would have avoided otherwise.

Charleston in South Carolina had a reputation as the murder capital of the US at this time. I didn't know that when in Washington DC, I couldn't find a bed for less than $20, so off to the bus station I went, and up on the board there was a bus to Charleston that was about to leave and would take long enough to give me a night's sleep.

It was one of my favourite places in the country.

In fact, there seems to be a correlation between how likely you are to get murdered somewhere, and how nice of a place it is to visit.

In these two months, I'd found my way to all four corners of the country, and many places in between. But the expiration of my Freedom Pass also marked the end of my time in the US. And what I'd done, was go onto Spirit Airlines' website, and look for the cheapest flight I could get out of the country from Miami, where I was right now.

"Bogota."

Well alright, I guess Bogota it is.

In 2022, Colombia's considered a great holiday destination. In 2009 this wasn't the case, and it still had a repuation as being the home of drug cartels.

My lack of awareness for personal safety hadn't paid much attention to this, and it was only when I started mentioning to people I met in Miami that I was about to fly to Bogota that they would stare at me for a moment, motionless, before saying something like "be careful down there."

I'd heard so much hearsay about how dangerous Colombia was, that by the time I boarded the plane I was convinced I wouldn't last the first night.

But it proved true again, that the higher the chance of getting murdered, the better a place is to visit. I loved Colombia.

I got there at exactly the right time. It was a beautiful, safe, friendly country. Perhaps the happiest place I've ever been. But no one else knew about it.

Like I said, the reputation that Colombia had within the US was that it was the land of drug cartels.

And I won't misrepresent things and tell you that I was the only tourist. There was a very established backpacking route through South America, and that included Colombia. To people who were already there, it was no secret how amazing Colombia was. But its reputation in the outside world stopped it becoming infested with tourists.

I stayed there for six weeks, even learning to dive. And when it came time to leave, I did so in a very Douglas MacArthuresque fashion, promising that 'I will return.'

Six weeks wasn't enough. It was the greatest place I'd ever been.

Diving in Taganga, January 2010

Diving in Taganga, January 2010

I spent the better part of a year in South America, meandering my way south through the continent.

As well as Colombia, there's no doubt that the other highlight was Bolivia. I stayed there for everyday of the 90 that they permitted me on entry, even stopping to spend a month learning Spanish.

I couldn't pick just one, but if you asked me to name the happiest moment in my life, it would probably something from these few months.

Quito, Ecuador, January 2010

Quito, Ecuador, January 2010

And on getting as far south as Argentina, my plan was to head back north again, keeping my promise to return to Colombia.

After this long backpacking, money was a little tight, and on arriving in Buenos Aires I secured my next income, again working as a lifty, although this time in the US.

I figured that by the time I'd made it back to Colombia, winter would just be starting, so it would all align perfectly.

La Paz, Bolivia, April 2010

La Paz, Bolivia, April 2010

Unfortunately, a short time later as I arrived in Paraguay, I was greeted by the news of a family bereavement that would mean my first visit to the UK on this trip.

My knee was still causing me a lot of discomfort, and back in a land of free healthcare, I took the opportunity to get it properly looked at.

When the injury had first happened back in Canada, I'd got nothing but an x-ray, because I didn't want to have to pay for anything more. The doctor had told me that there was likely some ligament damage, but I'd never had any confirmation of this.

Except it hurt.

Samaipata, Bolivia, May 2010

Samaipata, Bolivia, May 2010

You can become numb to anything if you experience it enough, and I'd had two continents to get used to the pain. But seeing as I was back on UK soil, I stayed long enough to get an MRI and get my knee diagnosed.

And thankfully there was no ligament damage, just cartilage.

I was told I'd need surgery at some point, but it wasn't urgent. So I did what anyone smart would do in that situation:

I went and worked another ski season.

The time this had taken made flying back to South America and continuing my trip north illogical. So instead, my girlfriend at that time, who'd I'd met backpacking in South America but who was going east anyway, came over and we spent some time travelling in Europe before I flew off to the US.

London, October 2010

London, October 2010

I'd had a great time travelling in the US a year or so earlier. Sadly, my experience of working there didn't match this, and I found American workplace politics uncompromising so as to drive you to despair.

For example, I worked on a ski resort. It wasn't as cold as it had been in Canada, where temperatures at the top of the mountain reached as low as -40°c. Here it was far more mild, rarely getting below -15°c. But it was still cold enough that when you were out on the mountain, you'd be covered from head to toe.

It didn't stop them having a rule where you had to shave everyday before work, and they'd check.

Despite the fact that the person enforcing this rule had a beard, the logic was that it looked more professional if the lifties were clean shaven.

Even on the warmer spring days, where my face was uncovered, I've never heard anyone go skiing and say "well, the snow was great, and skiing was great, and the weather was great. However, I had a really bad day because one of the lifties had a bit of stubble on his chin."

It was ridiculous.

I thought maybe it was just a bad job, so before the season's end, I got a summer job on the east coast, working as a bellman in a fancy hotel on Nantucket island, which might not sound too glamorous.

In fact, it wasn't too glamorous, I carried people's bags for a living. However, staff accommodation was included, so I had no rent and no bills.

On top of that, I made $11 an hour. But the tips. Oh, the tips. It was the kind of place where people would call us up, asking if they could land their helicopter on the hotel lawn. At one point, someone gave me $50 for carrying their quite small bag, from reception all of about 10 metres to their room.

The politics here, too, drove me insane. However, I stuck with it for as long as I could, just for the money I was making.

I eventually gave-in about four months into the season, and tendered my resignation. But by that point, I'd saved enough to cover everything that I'd spent in South America and then some.

As I was in the US on a working visa, the moment I resigned, I legally had 10 days to leave the country. And where was I going?

Where else? I've got unfinished business in South America.

I had some airline credit saved from an ealier incident where I'd been asked to change flights at the last minute, and I'd been compensated with $500 in credit for the inconvenience. Despite the direct flight they were moving me onto leaving later and arriving earlier than the route with transfer that I was initially supposed to take.

I'll take that deal all day.

So I used some of this credit to pay for a flight down to Fort Lauderdale, where I knew from experience there were cheap flights to Colombia.

At some point down in the Florida sun though, I had an epiphony.

"What is the point in travelling if you're just going to go to the places that you've already been?"

By now I had 2 days to leave the country, so on a moment's notice and with zero planning or research, I used the remainder of this airline credit to fly to Los Angeles, and the next day I was on a flight to Bangkok.

I didn't initially take to Thailand if I'm honest.

My knowledge of Thailand stretched about as far as I'd seen 'The Beach' once. But my initial impression, was that it was incredibly touristy, and incredibly tame.

South America had struck the perfect chord with me.

It was just touristy enough, where you would always be able to find a backpackers hostel to stay at, but not so touristy that you couldn't get away from it at times either.

And it had a bit of edge. I was lucky, but many people had a story about being robbed, or their bus being held-up at gunpoint somewhere, usually in Peru, or something along those lines.

No one had these stories in Thailand, it was incredibly safe.

I remember at the time thinking that it would be an amazing place to retire to, but that wasn't really what I was looking for.

Compared to South America where every country gave me a 90-day visa on arrival, in Southeast Asia, the custom is for 30 days.

And when you're like me, and don't really like doing things quickly, 30 days feels like a rush.

Mae Hong Song, Thailand, September 2011

Mae Hong Song, Thailand, September 2011

I made my way slowly north through the country, but it wasn't long before my visa was expiring, so I did what everyone else does, and crossed-over to Laos, just to come back in again for another 30 days.

Ah, bureaucracy.

I'm going to be honest, when I'd got off the plane in Bangkok a month earlier, I'd never even heard of Laos, but here I was.

I was staying at a hostel in Vientiane, and they had a little rooftop balcony. I was sitting up there, when I happened to glance at the notice board.

"Do you want a visa for China?" it said.

I... actually that sounds quite fun.

And that's how it happened.

Rather than heading straight back to Thailand, I got a visa for China, and made my way north through Laos, spending many, many hours on dirt roads in uncomfortable vans and minibuses.

Laos is a country about the same size as Thailand, but with 10% of the population, so in that regard, it's similar to Canada and the US. And where as in Thailand, I'd grown frustated with all the tourism, here it was much easier to escape.

At one point I was in the village of Muang Ngoi, which took an hour in a longboat just to get to; there were no roads.

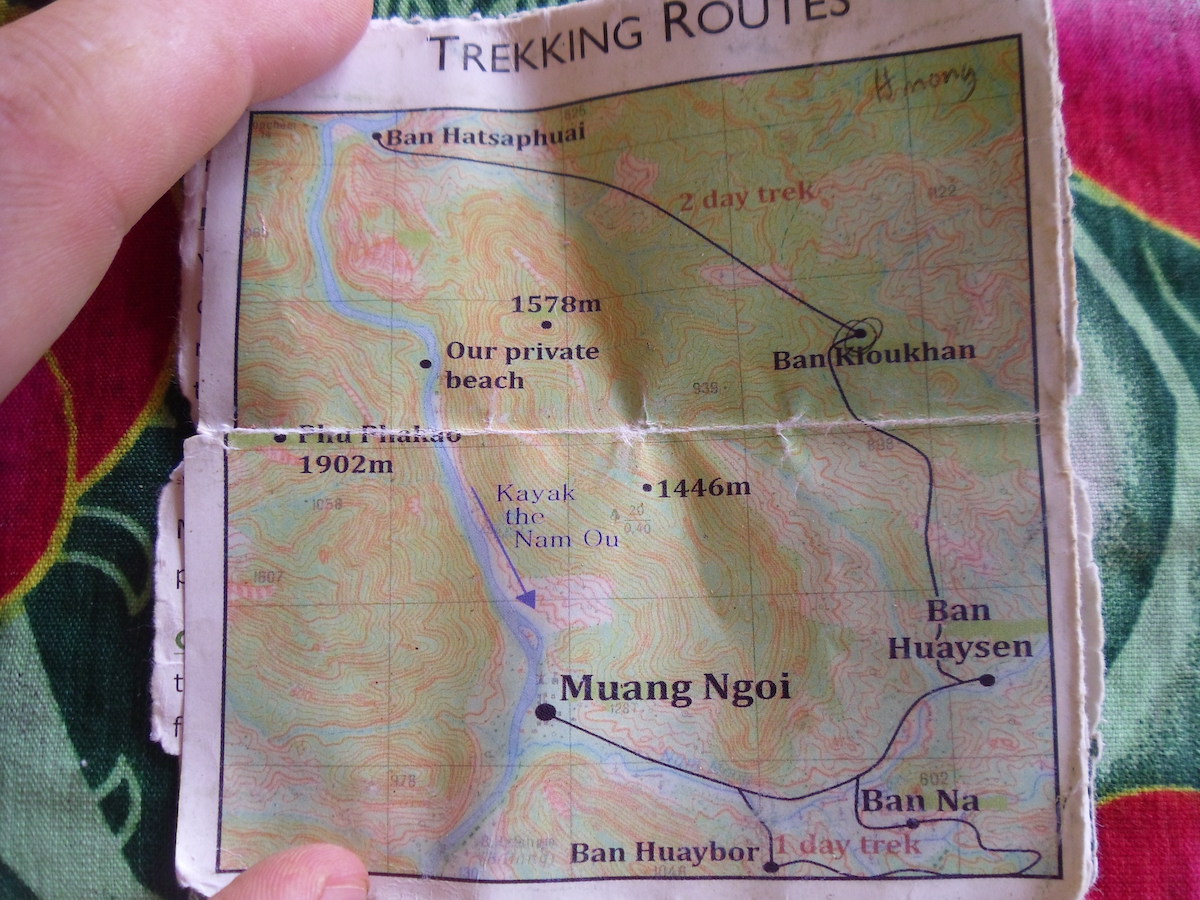

On my way in, I got handed a map no bigger than my hand, by some people who were going the other way, who told me that there was a Hmong village called Ban Kloukhan a few hours hike away.

What the Hell is a Hmong village?

Having a map is being pretty prepared for me, so off I wandered into the jungle to find out.

Turns-out there's a lot of leeches in the jungle, and they can smell you coming.

No matter how diligent you are in swiping them away, you constantly find them climbing up, and sometimes falling into your shoes. But you can't stop and take your shoes off, because there are so many of them, coming at you from all angles.

It was like a zombie apocalpse, with really, really small worm-like zombies.

I've never known fear like the moment I fell in that jungle.

When I eventually arrived in this village, not long before sundown, I had blood-drenched socks from all the leech-bites, and when I tried to talk to the villagers, the first ones looked at me like I was crazy.

"Well... this is going to be a fun night," I thought to myself.

Turns out wearing white socks wasn't the best choice

Turns out wearing white socks wasn't the best choice

Thankfully I was eventually able to find a villager who let me stay in his house.

I'd arrived in this village on the day of a wedding, or the day before a wedding. I never really found out. It wasn't too easy to communicate.

But they did let me... or rather, made me join in the celebration, which was basically everyone sitting around in a circle taking shots of homemade rice whiskey.

It was cool. I enjoyed my night in this village.

Ban Kloukhan, October 2011

Ban Kloukhan, October 2011

After initially only coming here as a means to get another Thai visa, I'd really taken to Laos, so it was again frustrating that I was only permitted to stay for 30 days. But I had my China visa, so I continued on north and took a bus across the border.

Well... this isn't what I was expecting.

My first stop on crossing the border was a city called Jinghong. I'd never heard of it.

And my assumption about China, was that it was going to be fairly rural, very underdeveloped.

Yet this city of Jinghong, a place that doesn't even feature in China's 50 most populated cities (I just looked) was lit-up more than Las Vegas.

Most places that I'd been prior to this had backpacker communities of some kind, and even if you went completely off the backpacker trail, you could rarely escape the tourism. The people there would still be used to tourists to some degree.

China was different. Sure, you could go to Shanghai, Beijing or a few other places and feel a part of the crowd. But to deviate from these areas, you could find yourself completely isolated.

With blonde hair and blue eyes, I stand-out in China, and people weren't afraid to stare.

At one point I took a route through some rural villages that took about a week. I didn't meet a person who spoke a word of English the entire time. Perhaps my most vivid memory though, was getting on a bus in one of these villages.

This was a stop for the bus mid-route, so when I got on, I was the only person at this stop, and the bus was already full.

It felt a bit like that scene from Forest Gump, where I walked down the aisle of the bus with everyone staring at me, but instead of saying "seat's taken" there was only one free seat on the bus.

In the back row. In the middle. With no seats in front of it, so in full view of everyone.

The moment that I sat down in this seat, looked up, and saw every single face on this bus turned around and staring at me will haunt me forever.

Litang, Sichuan, December 2011

Litang, Sichuan, December 2011

China was fascinating though. I loved it. There was always something going on, and it was the one place in the world where I had no idea how people would react to things.

I spent most of the time in every place I went just people-watching.

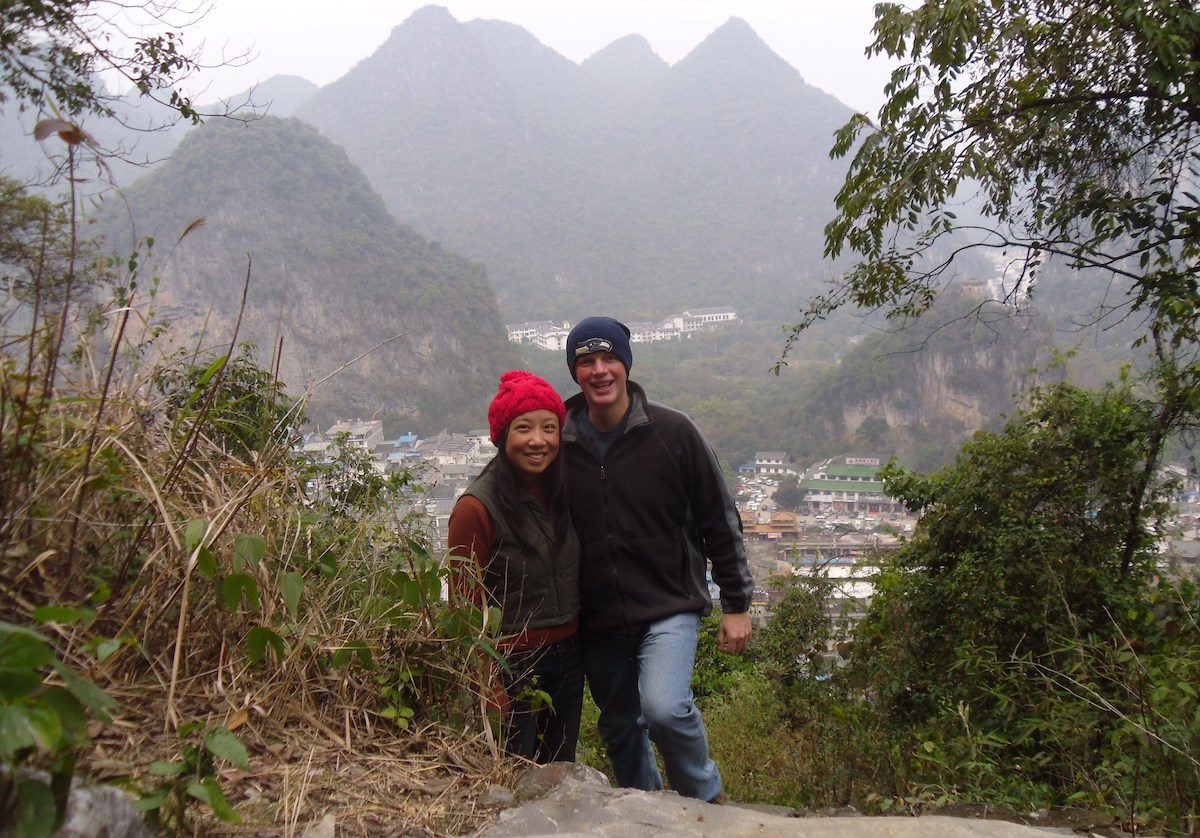

Yangshuo, Guangxi, January 2012

Yangshuo, Guangxi, January 2012

I'd gone in on a 30-day visa and jumped through the bureaucratic hoops to extend it twice, a process which as I found, can take 10 minutes or 1 week on the whim of the immigration agent. I didn't fancy my chances of getting a third extension though, so very reluctantly left China, crossing south into Vietnam.

After three months in China, anywhere I could go in Southest Asia was going to feel tame.

Forced to border-hop because of the 30-day visas, I went from Vietnam, over to Cambodia, back to Vietnam again...

For what had been only four months of work, the fact that I'd been able to afford this trip in Asia based off the money I saved working as a bellman in the US was amazing. But I was now reaching the point that I needed to garner some kind of income.

My plan was to go over to Australia. I'd got a 12-month Australian working visa issued by now, and I figured I'd give myself a head-start on the job hunt.

I remember a very specific moment, where I'd found a job ad looking for someone to do data entry.

That's never going to be anyone's dream, but I can type pretty quickly, and it pays well, so what the Hell?

But this is data entry. It's not customer service, or some specialised field. You just copy data from paper into a computer.

The moment that I saw the application form, and the ridiculous list of questions they wanted answered, for a job copying things into the computer, I just had a moment where I got this 1000 yard stare, and my mind switched.

"I can't do this anymore," I said to myself.

Backpacking... travelling... it's a dream to many people, but anything, no matter what it is, stops being exciting when you do it too much.

Not only could I not face another year of working unskilled jobs, this time in Australia, but I didn't really know what I was doing it for.

After the ski season I'd worked in Canada, I'd "backpacked" around the country for 7 months, then 2 more in the US, then the better part of a year in South America, then Europe, now 9 months in Asia...

I was just, kind of, over it.

Going to new places wasn't exciting anymore. I'd stayed in backpacker hostels numbering in the hundreds. I had no motivation to spend another year working dead-end seasonal jobs, just to do it all again somewhere else.

And right there, at that moment, with this data entry application form in front of me on my laptop, I decided to change everything.

I'd always thought about teaching English. It's the one gift that as a native speaker, you have and the whole world wants. As a native English speaker, you can get a job pretty much anywhere in the world. I'd just always been scared of teaching. It was a completely foreign skill to me, but the choice was to face that fear, or go to Australia.

I'd obviously had hundreds of conversations over these years with people travelling abroad, working abroad, living abroad, teaching abroad, so the second I decided this, I already knew what I wanted to do.

The reputation of English teaching qualifications, was that TEFL was what you took if you were a backpacker who wanted to teach overseas for a few months, but if you wanted to turn teaching English into a career, you took a CELTA.

That stands for 'Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults', and in this little cafe in Vietnam, I immediately got on my laptop to look up nearby places to do a CELTA.

Of all the places that I'd been in Southeast Asia, I'd really fallen in love with Saigon/Ho Chi Minh City. It was just a fun, vibrant city.

I hadn't known too much about the Vietnam war on first coming to the country, so it was quite cool to learn about it from the non-western perspective.

Captured American helicopters and tanks and armoured vehicles were on display as trophies throughout the country.

Hue, Vietnam, April 2012

Hue, Vietnam, April 2012

As one of the touristy things to do, I'd gone to the presidential palace in Saigon, and on wandering around, I found they had a little movie theatre in the basement where you had a choice of DVDs about the Vietnam war that you could put on.

There was no one in there, so I put on a DVD about the fall of Saigon.

There was something very special about learning how the tanks rolled into Saigon and took over the palace, while I was sitting in the palace.

Normally history seems like something that happened in another time in some distant land. This made it feel a bit more real.

If you'd told me at that moment, that I had to pick somewhere in Asia to live, I'd have picked Saigon. And there just so happened to be 2 schools in Southeast Asia where you could do a CELTA. One was in Saigon, one was in Bangkok, and so that's an easy choice, right?

I went to the one in Bangkok.

The Saigon school had some dubious reviews, where as the one in Bangkok had a stellar reputation.

The CELTA wasn't cheap; it was a $1,500 course and took a month to complete.

Spending that kind of money when you're on a backpacker's budget is akin to a normal person buying a house, so I wasn't going to leave anything to chance.

You needed to have an interview to even get onto this course, and that could be done over the phone.

I told them that I'd be there in person. I wanted to see the school for myself.

So I hopped over the border to Savannakhet in Laos. Unbeknownst to me, it was the Lao/Thai new year, which meant that everyone, everywhere, was throwing water at each other. Which was a lot of fun, once I'd found somewhere to stay and had stashed my belongings. Before that... not so much.

The real downside though, was that I had this interview on the first day after the new year, and going over the border again, back into Thailand, it turned-out all the buses to Bangkok were sold out.

Great.

I was able to make it to a train station about 100km south of where I'd crossed the border, knowing full well that 3rd class train tickets are unlimited.

I'm not really a prude when it comes to travelling. Every flight I've ever taken has been in economy class, I've had multiple bus journeys of over 50 hours, I've spent God knows how many hours cramped up in vans and minibuses on dirt roads in South America and Asia, I regularly take 3rd class trains where they're available.

This journey though, this train journey to Bangkok sticks-out in my mind as the most gruelling of all of them.

Not because of the train itself; I was used to 3rd class. But because of the sheer weight of people travelling back to Bangkok at once after the holiday.

There wasn't even space to sit on the floor, you had to stand, tightly pressed against the people around you. Even the toilets had people compressed together in them. I had my backpack at my feet.

I think it was only 10 or 12 hours on this train, but my God it felt like a lifetime. I've never been so relieved for a journey to be over.

It didn't really put me in the best headspace for an interview the next day, but I was quite impressed with this school, so... I guess I'm studying a CELTA in Bangkok.

As had become the custom for Southeast Asia, I then had to leave the country again, just so I could come back later with a visa long enough to complete the course.

That took me back to Laos, coinciding with the Vang Vieng rocket festival, which is as much of a health and safety nightmare as it sounds.

The logic is that if they fire rockets high enough, it'll piss off God and in response he'll make it rain, and that'll start the wet season.

So everyone in town, while very, very drunk, is carrying around homemade rockets that quite literally fire over mountains. It's madness, but it did make for a good party.

Vang Vieng rocket festival, Laos, May 2012

Vang Vieng rocket festival, Laos, May 2012

I'd been warned about the intensity of the CELTA, but it definitely lived up to its reputation.

There were classes of students, mostly refugees, who couldn't afford to study English in a paid school. On the first day of this course, we were told the teaching rota, on the second day, I was teaching English to a class of 30 of these students.

I don't get nervous easily, but I was petrified before that first class. The course was a complete baptism by fire, and one of the hardest things I've ever gone through. Harder than any job I've ever had, we taught and got criticised throughout. But my God, if the goal was to get you as good at teaching as you could be in four weeks, it was very effective.

I... survived the CELTA, a course administered by Cambridge University. So I got a graduation certificate from Cambridge University after all.

And there was a careers councillor on site, or at least someone moonlighting as one, to help graduates get started after the CELTA, so I made sure to sit down with him, and learn what I could about getting a job in Saigon.

From that conversation, I somehow ended up with an interview at an adult school in Bangkok under the premise of 'it can't hurt to talk to them,' and they offered me a job, and I accepted and... oh, I guess I'm staying in Bangkok then.

My logic for becoming a teacher had been that I was kind of tired of backpacking, and also the unskiled work in between in order to pay for it. But I didn't want to go home yet either. I wasn't done exploring the world, and I wanted to be more than a tourist in the places that I went.

And what's the one skill that I have that can allow me to work anywhere in the world?

It was always meant to be six months here, six months there, teaching my way around the world. So when I accepted this job in Bangkok, in my mind it was no big deal, because I didn't plan on doing it forever.

But then you end up getting a condo, and then you buy things for that condo, and before you know it, you're living in Bangkok.

The whole time I was there, I was very conflicted.

I didn't want to stay there forever, but also I was pretty comfortble. And comfort's a very dangerous thing.

It's something that everyone strives for. We all want to have money, so we can be comfortable. We all work hard, in order to be comfortable. But why?

If you go to the gym, and only ever lift weights that you're comfortable with, you don't get stronger. If you go for a run, and stick with a pace that you're comfortable with, you don't get fitter. In coding, if you only work on features that you're comfortable with, you don't get better.

Comfort is a recipe for stagnation, and yet for some reason, we always strive to have it.

Compared to a Western salary, I was earning a pittance; I could never have survived on it in London. But for Bangkok, it was three or four times the average. I was living like a king, in great comfort.

It took a year and a half until I left my job, and I easily could have got another one in Bangkok, but I decided to move on somewhere else; that was why I'd become an English teacher after all. And I knew already where I was going.

For better or worse, China had absolutely fascinated me when I'd had three months backpacking there. It was a place that I wanted to go back to, and to be more than just a tourist.

In Bangkok, I'd been working at a private adult school, and although I met some amazing friends and have some good memories, their lust for profit, and consequently how they treated people, both students and staff, meant that I left there with some negative memories as well, and I didn't want to replicate such a job in China, so instead I looked at universities.

At first I tried to find universities who were advertising for English teachers, but I quickly realised that many didn't, so I just started sending off cold emails to universities, asking for a job. And I got offered many.

That's not a reflection on me in any way, rather that the number of people willing to go and live somewhere pretty much correlates to how much tourism there is there. Bangkok is one of the most visited cities in the world, so the people who like it and who decide to settle down and teach there means that English teachers are a dime a dozen.

Outside of the main cities, China is the opposite, and I wanted that.

I ended up accepting a job in the city of Changsha, which I'd never heard of. Although as I heard many times when I was there, the university's alumni includes Chairman Mao, so... well that's one claim to fame.

I lived on the university campus, which was right on the outskirts of the city.

Leave the campus and turn right, you can take a couple of buses and be in the city centre. Leave the campus and turn left, and within two minutes of walking, you're among fields.

There were a couple of other foreigners working at this university as well, but beyond that you had to travel miles to find the next westerner.

It was the kind of isolation from western influence and the kind of immersion into Chinese culture that I really wanted.

It was no doubt the best job that I'll ever have.

It was the only time in my life that I've worked for the public sector, as I was employed by the Chinese government. And the benefit to that, was that having no one seeking to pad a bottom-line, and to squeeze as much labour out of you as possible, the hours were glorious.

In one of my terms there, for example, I taught on the Wednesday and the Thursday afternoon, so for about six hours in total. I was off from Friday to Tuesday.

Somehow I was considered a full-time employee.

I also got paid holidays, and being a university, these were substantial; I think four months off in the summer alone.

I'll never have a job like that again, and living on campus, I had a running track two-minutes from the flat where I lived. I knew even then that this was the best job I was ever going to have.

And I really enjoyed living in China. I got to know my students, and to understand the culture very well. It was an amazing experience.

However, given how isolated I was, it was also a lonely one, and that was why I ultimately decided to leave.

I'd gone there on a six-month contract, and I extended it twice. But I was also aware that I wouldn't stay there forever. It was just very hard to leave this job. Wherever I worked next would be a step-down.

I was only earning about £500/month in China, but with accommodation and bills included, this only had to cover food and leisure, so by the time I left I'd managed to save about £3,000.

That was about three times more than you were allowed to take out the country, so on leaving I closed my bank account, withdrew all this cash, and spread it as thinly through my bags and on my person as possible, in the hope that if they found any of it while I was going through immigration, they wouldn't find all of it and would think I was under the threshold.

It worked, and I made it out with my money, back to the UK.

This wasn't the end of my trip, but I wanted to go home and see family. And although I didn't know for sure where I was going to go next, I told myself that if I hadn't had any better ideas by the end of the month, then I'd take a flight back to Bangkok and figure it out from there.

And that's what I did.

As I said earlier, I hadn't initially taken to Thailand when I'd first arrived, but on living here previously, I'd really fallen in love with Thailand, Bangkok especially. And so, with no better ideas, it seemed the logical place to go back to.

I'd now been a teacher for more than three years, and had learned a lot about what I wanted from a job. So rather than just accept the first one offered, which I was more likely to do while inexperienced, I knew the value of having a job with plenty of holiday and time off.

I'd just left a full-time job where I worked six hours per week. There was no way I could go back to forty or more.

After about three weeks I hadn't been able to get an offer from anywhere that I was willing to work, and so was getting ready to leave Bangkok and head to the north of the country one morning, when my phone rang.

I knew other teachers in Bangkok obviously, and so I had a very good idea of the best places to work, and so the first place I'd applied to was the one school that I'd really hoped would accept me, mainly because they worked six-week terms, after which you got a week off, and they allowed you to take one term off per year.

Combined with the other holidays, like Christmas and Thai New Year, that came to 16 weeks off per year, which wasn't quite what I'd had in China, but was about as good as I could hope to get.

Having applied to this school and heard nothing back, my hopes of getting a job there had long faded. But here I was, bags packed and about to leave Bangkok, when my phone rang, asking me to come in for an interview.

I guess I'll unpack my bags again then.

In a change of management, my application for this job had slipped through the cracks, but thanks to another applicant being more forthcoming in chasing-up her own application, mine too was found.

I got this job in Bangkok, so what was the next logical step?

Yep, I had to leave the country.

Seriously, who comes up with these rules?

It was back to Laos in order to come back into Thailand on a different visa. And whereas in my first time living in Bangkok, I always expected to leave at some point, and during my time teaching in China, I always expected to leave at some point, this time I... just didn't.

Each time I built a life for myself somewhere, only to tear it down to nothing but a backpack, only to rebuild it elsewhere, it got harder.

Whenever I weighed my bag at the airport, while moving to China, or back to Thailand, it weighed less than 15kg.

Each time I left somewhere, I had to get the total possessions I owned in the world, down to 15kg, and I was just kind of over it.

Although I'd become an English teacher in order to work as I travelled, I didn't really have that desire anymore.

There were definitely moments where I would start to envision my life in Bangkok ten years from now, twenty years from now...

And while these were a sign that I was now more settled than I had been in my adult life, they also came with a problem.

I loved my job there. The students were really fun, the managers were always fair, and there was enough time off that I could have a life outside of work

Other people felt the same, and when I looked around the staffroom, we had multiple teachers who'd worked at this school for over 20 years, many who had worked here more than 10. And I could look at these teachers, each of whom had started at this school under similar circumstances to my own, and really see my future.

For however settled and at home I felt in Thailand, the reality was that I was only in the country on a working visa. And were I to leave my job, I would consequently have to leave the country.

There would be no prospect of retiring and staying in Thailand, not on my current visa at least.

I also wasn't making a tonne of money.

I was earning great money for Bangkok, and saving plenty. But converting that to pounds, I wouldn't be able to save enough to retire in the UK; not even close. And I wasn't paying any National Insurance in the UK at this time either, so I was doing nothing to pay towards getting a state pension.

If I stayed on this path, my future prospects were quite chilling, and I got to witness others who'd stayed too long, and were living exactly what I feared. Because the problem is, that when you're earning a well above average salary (for Bangkok), then it's very hard to leave, and to go home, where you have no transferrable skills; English teaching is not lucrative in England for obvious reasons. So you are going to wilfully leave your comfortable job in Bangkok, to go back to London and work a minimum wage job, just to have a pension in a few years?

Plus, Thailand is a very comfortable and welcoming place. Regardless of the money, it's hard to leave that and go back to London.

So you don't, you just stay there. Getting deeper and deeper into this dilemma, where your years until retirement become less and less, but you have no pension and nothing to fall-back onto, and you can't even leave your job, because you'll then have to leave the country.

I witnessed this first hand. We had a teacher in the staff room who'd started working at this school in her forties. She was now 84, but had to keep on working. We had another guy in his seventies, who called-in sick one day.

He never made it out the hospital. Literally had to work until he died, and I could look around the staff room at other people at various stages along this timeline, and I really had to look in the mirror and think... do you want that to be you?

Comfort is a dangerous thing.

By this point I'd worked at this school for two years, and so what I did was tell myself, "ok, you can work here for one more year. Use that year to figure-out your future. But no matter what, you need to quit this job 12 months from now."

I put this timer, this sword of Damocles over my head, and I had 12 months to figure-out the rest of my life.

I had a small number of pipe dreams that I explored. For example, despite hating reading myself, I've always wanted to be a novelist. And so one day, I sat down at my laptop and I started to write a book.

I got about 5,000 words into it, before my brain dried-up and I was all... I've got nothing else to write.

Alright, I guess I'm not supposed to be a novelist them.

As a (relatively) young person, I'd been brought-up on computers. I could turn a computer on and off, and use Microsoft Office as well as the next guy, but that was as far as my knowledge went.

The one effort I'd made to improve this was signing-up to a computing A-level course 15 years earlier, and I'd given that up after one class.

However, another of these pipe-dreams, was that I wanted to code.

Partly that was down to it being something that I thought I would be good at, because I'm a very organised, analytically-thinking person.

I like to play Sudoku and Tetris, and I thought that my mind was naturally suited to coding.

It was also because there were iPhone apps that I thought ought to exist, but didn't.

Mostly related to health, and the amount of health data that our various devices collect on us, I thought then, and still think to this day, that it could be utilised so much better. It's such an amazing trove of data on how our actions impact our health, and it's served by the likes of Apple as nothing more than some useless graphs.

Even by this point, I'd felt this for years, and I'd posted my ideas on 'app idea' forums, where people post their ideas for an app, in the hope that someone picks it up.

And I'd just got the point of... alright, fuck it. If no one else is going to utilise this data in a useful way, then I'll learn to code and I'll do it myself.

That was my dream. But at this stage, I had a four year-old Windows laptop that had only cost me £300 to begin with, took about 30 minutes to warm-up, and could barely handle Microsoft Word.

To explore this coding dream, I was going to need to upgrade my hardware, and I spent weeks researching, and going to shopping centres to try out various MacBooks.

Spawned from my backpacking, I had, and still have this attitude when it comes to money where you never spend more than you need to, and if you're ever in a dilemma about whether or not to do something, always make the choice that costs the least money.

So the idea of me going and spending £1,500 on a MacBook, just to explore this pipe-dream of learning to code, which could die-out as soon as my dream of becoming a novelist had, it was a very hard sell.

I had to be at least semi-sure.

And after weeks of contemplating and researching, I went down to this shopping centre in central Bangkok, and I spent the equivalent of £1,500 on a brand new MacBook Pro.

Well... at least I've got a nice computer to plan my lessons on now.

Time is Swift

As my dream was to create these iPhone apps that I wanted to exist, the logical choice was that I'd learn to code in Swift. So my introduction to coding was a Swift course on Udemy. And you know what?

I loved it.

If I'd said that I understood everything that I was learning, it would have been a lie. Even the most dumbed-down course is going to be taught by someone who can't put themselves on the level of someone with no coding experience.

However, even at this stage I was very comfortable figuring things out for myself. And for as stressful as I found it, the ecstasy of fixing a bug and finally getting my code working, made it all worth it.

At this point, I was still working full-time as an English teacher, and would code in my free time.

The unfortunate thing was that this free time wasn't always available.

In my time in this job, I'd had two amazing managers. They'd always been receptive, and had always done everything that they could to make the teachers as comfortable as possible, by giving us classes that we'd taught before, and giving us our preferred hours.

That was what allowed me to have free time, where I wasn't too tired or stressed-out, and could study coding.

Sadly, both of these managers suffered the same fate.

I was working at the head-office branch of this school, which had campuses all over Thailand. And being the manager of the head office branch, meant that you had oversight that wasn't present anywhere else. And they'd both had enough of it, and transferred to other branches to be free to do their jobs.

As rumour has it, for this reason they couldn't find anyone to take on the manager's role at my branch, until they finally had to settle on the only person who wanted the job.

What that meant for the teachers, was gone were the favourable schedules, without too many classes to plan, and where we were able to work the hours we wanted.

Instead, this new manager went out of his way to make everyone's lives as difficult as possible.

Split-shifts, where you'd have one class in the morning, and one in the evening.

You could find another teacher, who had a morning class at a different time, and an evening class at a different time, and ask this manager, "can we swap, so he only has morning classes, and I only have evening classes?"

He'd answer with a dictatorial response about how he makes the decisions.

Overnight it went from being this amazing job, to one of stress, and working excessively. Even during time-off, you had so many different classes to prepare for that you never really stopped working.

This was immediately reflected in teachers resigning or transferring to other branches.

What it meant for me, was that I'd gone from having the time to code almost everyday, to being lucky to find one hour per week.

The coding knowledge that I'd accrued was leaving my mind faster than I could put it back in, which put me in a very awkward spot.

If I can no longer learn to code while doing my job, then I've got to make a choice. I've either got to leave my job and focus on this pipe dream of coding, or I've got to forget about this dream and focus on my job.

At this point, I had 6 years of experience as an English teacher. Although things had got worse recently, the belief around the staff room was that this manager couldn't last long; probably not even a year, because everyone hated him. So all I really had to do was wait it out.

As for the teaching itself, I remember when I first started, getting stumped by what I'd now consider really, really simple grammar questions.

But when you've taught a subject for six years, you've essentially taught every grammar point that you're ever going to teach, and been asked every question that you're ever going to be asked.

Maybe once every three months, I'd be asked a question that I'd never thought about, and have to stumble my way through answering it. But that was about as awkward as my job ever got.

I was very comfortable being an English teacher.

I'd now spent a total of about five years in Thailand, and I earned well above the average salary. And to leave my job to focus on coding, all of this would go up in smoke.

I'd no longer have my Thai visa, I'd no longer be working a job I was comfortable in, I'd no longer be earning an above average salary. I would be someone unskilled trying to break-into a skilled industry. And despite the promise I'd made myself 12 months earlier to finish working as a teacher no matter what, pulling the trigger and actually doing it was very hard to do.

I was very aware that were I to do so, my life would get worse before it got better. And it's a hard thing to knowingly and wilfully make your existence harder.

And even if I did quit my job to focus on coding, how exactly would I do it?

The extent of my knowledge to this point was a Udemy course that I'd only been able to sporadically dip-into of late, and I'd started learning from the 'Hacking with Swift' book as well, as a way of filling-in some of the gaps in my knowledge.

Do you ever have moments that seem so insignificant at the time, but when you look back they ended up changing the entire course of your life?

For how bad things had become, almost every teacher was now talking openly about leaving this job, so we'd chat in the staff room about what it was we were thinking of doing instead.

I happened to mention to one other teacher during one of these conversations, that my dream was to learn coding. A few days after that conversation, she sent me a Facebook message.

Hey, just came across this article, and since we talked about this recently I thought I’d share it. Sounds very much like a cliche, but what he says about education is so true, and this might be inspiring.

She then added a link to this article titled 'How I landed a full stack developer job without a tech degree or work experience,' which details the author's own experience of going to a bootcamp in order to get a coding job.

Up to that point, I'd never even considered a bootcamp.

I'd been planning on self-teaching in some way. In order to stretch my savings as far as possible, I was really thinking about finding some secluded corner of the world in a cheap country, and just locking myself away and coding everyday. But this article spoke to me.

Learning to code while working a full-time job, it didn't really matter how long it took me, but if I were to quit my job, I'd be on a timer.

I'd have until my savings ran-out to make myself employable, so I was really seeking the way to earn an income from coding in the most efficient manner possible.

One of the initial benefits to my teaching job, was that I could take one term off per year, and thankfully I'd got my term off this year confirmed under the previous manager, because the new one was determined to stop this practice.

I used this term off to go back to the UK, and although I didn't say a word to anybody, when I left the school to take this 8-week break, I cleared-out my locker, because unlike in previous years, I didn't know if I was coming back.

It was a slightly weird feeling walking out of the school that day, after working there for three years, not knowing if I'd be back again.

I still hadn't handed-in my notice, I still hadn't been able to commit to giving-up on the comfort of living in Bangkok. But I knew there was a possibility that I wouldn't be here again, so I cleared-out my locker just in case.

I just had to see if, during this trip back to London, I could find the steel to once again, give up my life and pack it into a 15kg suitcase.

In this article, which I very much looked-at as a blueprint for becoming a software engineer, the author had gone to Le Wagon bootcamp.

That was by no means the only research into various bootcamps that I did, but I continually read good things about Le Wagon.

They have a campus in London, so during my visit home, now in August 2018, I visited the campus, I talked to the teachers, I talked to the students.

This was the push I needed. It just felt right. This was my future.

At this point I was 32; almost 33.

The way I was looking at it, was that being in my early/mid thirties, I was still young enough that someone would be willing to take a chance on me. That I would be able to walk into a job interview having no coding experience, and someone would give me a shot.

I didn't have the faith that would still be true at 40.

I'd seen first-hand as a teacher, how the older a person gets, the harder they find it to learn new things.

In order to learn what I needed to learn, and to get the subsequent opportunity at the bottom of a career ladder, I convinced myself that it had to be now.

After visiting the London Le Wagon campus, I messaged my school in Bangkok and gave them my notice, but with about five weeks of holiday remaining, this meant that I would never teach there again.

Teaching in Bangkok, July 2017

Teaching in Bangkok, July 2017

I then had to start shutting my life of three years down into a 15kg suitcase, and that started by messaging my landlord and telling them I was moving out.

With London being my hometown, family I could stay with here, and Le Wagon having a London campus, the obvious choice was that I'd attend the bootcamp here.

Now was August. I needed some time to shut-down my life in Bangkok, so the next Le Wagon batch I could get onto would be November.

London, in the middle of winter. Learning to code in this stressful bootcamp, about 90 minutes away from my house in each direction.

Do I really want three hours per day sat on a train during this bootcamp, where the train fares would be as much as a night's accommodation somewhere cheaper?

Seeing as I had to go back to Bangkok anyway, I ultimately decided to do this bootcamp in Bali.

The bootcamp

Le Wagon, Bali campus, October 2018

Le Wagon, Bali campus, October 2018

The reason, or one of the reasons I chose Bali, was that being as stressful as I was anticipating that the bootcamp would be, being a stone's throw from the beach would be a God-send in keeping you sane.

Not being in London would also mean that I could find some accommodation right by the campus, and the cost of living in Bali would be so much lower than the other cities I was considering (Barcelona and Tel Aviv).

My main fear countering these benefits, was that being the holiday destination that it's known as, people would come to the bootcamp in Bali and to them it would be a holiday, and I'd find myself working with some very unmotivated peers.

So I had a few 'come to Jesus' moments with myself before I left Bangkok, where I really focussed my mind on what I wanted from this, and how I wanted it to go, promising that I wouldn't be swayed by the actions of others.

The bootcamp itself cost around £5,000. Adding on the cost of living for two months, it was more or less going to drain my savings.

While some of my peers seemed to come here on a whim, or as something to do, for me this was my future. If it went wrong, I'd be unemployable and out of money, and the best I'd be able to hope for would be teaching English again, which I was trying to escape.

So where as others went out, and socialised, and learned to surf, I did none of that.

I'd code from 9am to 7pm everyday as the campus was open. Then I'd take my laptop back to my room and code until bed. I'd code on weekends.

Where my attitude lay, was that if I gave it 100%, and I still failed to make it as a software engineer, then ok, I can live with that.

What I would regret is failing after not giving it my all. Failing, but then thinking "well at least I learned to surf. As least I had some fun night's out in Bali."

And I was right with my fears. As the bootcamp progressed, I saw my peers become less and less motivated, getting to class later each day, leaving earlier.

I did a lot of meditation; often 30 minutes a day through the bootcamp, to really keep myself focussed on my goals, and to not grow any antipathy towards the people who were setting examples that I didn't want to follow.

As for the bootcamp itself, there was a curriculum to follow, lectures everyday, and teaching assistants on hand to help you.

Despite this, I was determined to take responsibility for my own learning.

I'd spent the last six years in classrooms, and I'd seen the kinds of people who learned, and those who didn't.

Every class I taught would have some people in it, who took responsibility for their own learning, and other people who thought that by showing up they'd done enough, and from that point it was the teacher's job to put knowledge in their brain.

For me, the bootcamp was just one tool, but success was going to be determined by the knowledge that I left here with, no matter how I got it. So any day where I didn't fully understand a concept, going online and researching it myself was my evening/weekend task.

It was a very intense way of learning, but it was effective.

As one of the teachers, who'd gone through the bootcamp themselves three years earlier, said to me, "it's like clinging onto the side of a high-speed train."

What he meant, was that through the sheer volume of knowledge that we learned in such a short space of time, you did feel at times completely panicked and overwhelmed, but if you clung-on, you ultimately you got to where you wanted to go.

And that was being able to build a fully-functioning web application.

The bootcamp taught Ruby on Rails.

We started by learning Ruby. Then we moved onto object-oriented programming, followed by a module on databases, and next was front-end development.

Finally, when that was all done, we moved onto Ruby on Rails, which brought it all together.

The final projects were done in groups of four, where we had to collaborate in order to build a Ruby on Rails app in time for "Demo Day", where the app would be presented.

In my group, we built an app called 'Buidl' (don't ask), whose goal was to use the Github API to visualise a person's Github profile in a way that you could enter someone's Github username, and be presented with graphs about the types of projects they built, the languages they used etc.

If I said that this had all gone smoothly, it would have been a lie. If I'd said that I'd not felt completely overwhelmed for the last two months, it would have been a lie. But we did it. We got there.

As I'll continue to say, you don't improve at anything by being comfortable. You've got to challenge yourself and to push yourself to breaking-point to know what you're capable of, and that's what this bootcamp did.

But when I looked back over it, where my goal had been to come here and to learn as much as possible, I couldn't help but think... 'well it worked.'

The job hunt

As a group who two months earlier, had little to no coding knowledge, and who knew little to nothing of Ruby on Rails, we'd been able to build this fully-functional Rails application.

Learning to collaborate while coding was probably the most valuable skill that I took away from the bootcamp, but it also presented a problem.

We, as a group of four, had built this application. Which meant that I had only built one quarter of it.

Now, away from the bootcamp and alone, could I still build a functioning application?

Prior to Demo Day, I hadn't drunk alcohol in nearly four years.

I'd gone through a very health-conscious few years, and with hangovers getting worse as I got older, I'd decided that my body was telling me that the party was over.

I never intended to go four years without drinking, but the longer I went without a hangover, the less I wanted to have one again, so I just stuck with it.

The final day of the bootcamp was the moment where I was like... alright, screw it. After these two months, I need to have some fun.

When you haven't drunk in four years, that's a fun party. I woke-up still drunk at about 7am the next morning, and you know what I did?

I pulled-out my laptop and I started coding.

For as fast as knowledge had gone into my mind over these last two months, it would leave just as quickly if I didn't continually reinforce it, so I was determined that no matter what, I had to keep on coding, every day.

In fact, now without the structure of the bootcamp, I had to be even more disciplined, and I coded like I never left.

Another reason that I chose coding as my post-teaching career, was that I still wasn't really resigned to going back to London or anywhere else to settle down permanently.