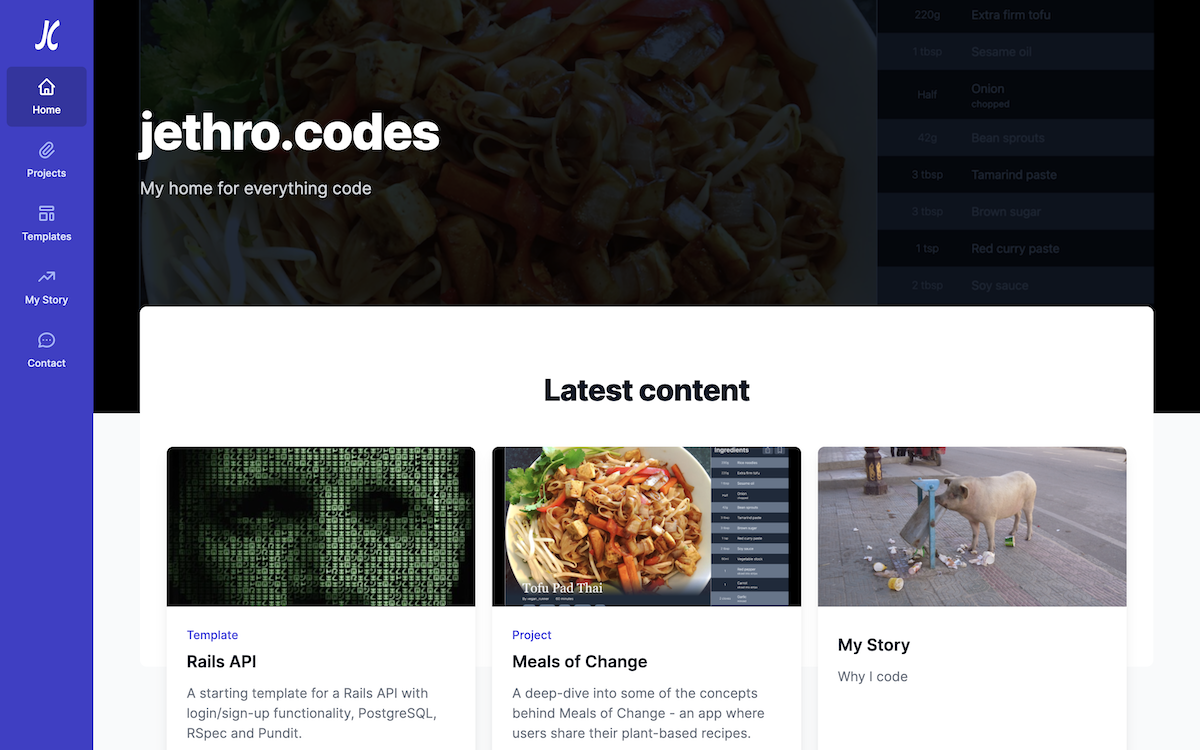

jethro.codes

A look behind the mechanics of how this app utilises Markdown files to automatically update the homepage and other pages.

Note: At the time of writing the below article, this app was hosted at 'jethro.codes'. Subsequent to hosting it there, the price of the domain increased about 1,500%, so I have since moved it to 'code.jethrowilliams.com'.

I wasn’t going to write an article about this app, because I thought it’d be a bit weird to write about an app within the app. Some kind of appception.

I imagine that’s what the people who make Git go through everyday.

However, in creating this app, I learned a lot that I didn't know before, so I think it’s worth going over and hopefully it can be useful.

Being an app consisting mostly of articles, it made sense to me that I’d write them in Markdown. And what I wanted, was to be able to add a Markdown file, and by simply adding this file and doing nothing else, I wanted the homepage to update, the section page (for example, the 'Projects' page or the 'Templates' page) to update, and even the sitemap to update.

I had a rough idea how I could achieve this, but then I found that Vercel had a template project that was better than my idea, and using that as my starting point, I was able to build the foundations of this app so it does exactly what I wanted.

I added this article as a Markdown file, and by doing nothing else, as if by magic it appears on the homepage, the projects page, and in the sitemap.

Background

My reasoning for creating this app was fairly simple.

At this point, jethrowilliams.com was already online, and that was my sort of... front page.

If I want to give someone a very quick overview of exactly what it is I do, and how they can contact me, then I can direct them to jethrowilliams.com. And for the majority of people, that’s going to be enough.

However, this front-page doesn’t allow me to go into any depth on the code I create because most people, especially non-technical people, just don’t care.

So I wanted a place, partly for my own benefit because I find it insightful to have to explain something in a manner that others can understand, where I can go into more depth on the code that I write.

As coincidence would have it, I already owned the domain jethro.codes because, on putting my name into the Namecheap app in a moment of boredom once, I stumbled across it, it was available, and it had a 90% discount.

So I figured, for £3 I’ll buy it for a year. If I think of something to do with it, great. If not, it's cost me less than a cup of coffee.

And I don’t drink coffee, so I had nothing to spend that money on anyway.

Styling

Before I get onto the technical side of this app, a quick word about styling.

This app may look like it was cobbled together with a bunch of random components that don’t have any relation to each other. And that’s because... well it was.

Up to this point, every app I'd ever made I'd done the styling myself. And although I enjoy and I'm good at styling, it's such a time consuming process, tweaking every element for various devices and screen sizes.

I just wanted a place where I can write about code, and in all truth, so long as it doesn't look completely atrocious, I'm not too concerned with how it looks.

So while I have done some minor customisation, this app is largely made up of Tailwind UI components.

Again, with some minor customisation, the Markdown articles themselves are styled with the Tailwind typography plugin.

The Tailwind docs are some of the best I've ever come across, and do a far better job of explaining how to use these features than I ever could, so I won't say anything more about the styling for jethro.codes in this article, because I spent very little time on it.

What I instead want to focus on is fetching the Markdown articles, and updating the app accordingly.

Structure

Before getting into the API and fetching the articles, it's worth mentioning the stucture of the app to make everything a little clearer.

This is a fairly standard Next.js app. It was started from my own next-js-template project, which in turn was started from create-next-app. I won't go into any more detail about what Next.js is, or how to start a next project in this article; I'll assume that you know the basics.

Below is a file tree of all the files/folders relevant to what we're going to cover in this article.

📦 _articles

┣ 📂 projects

┃ ┣ 📜 jethro-codes.md

┃ ┗ 📜 meals-of-change.md

┣ 📂 templates

┃ ┗ 📜 rails-api.md

┗ 📜 my-story.md

📦 lib

┣ 📜 api.js

┗ 📜 markdownToHtml.js

📦 pages

┣ 📂 [section]

┃ ┗ 📜 [slug].js

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 contact

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 my-story

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📜 _app.js

┣ 📜 index.js

┗ 📜 sitemap.xml.jsTo start with, the _articles folder is where the articles are added as Markdown files.

The pages folder shows the pages within this app.

The api.js file in the lib folder is where all the magic happens. This is where the logic to look within the _articles folder and return the correct data to the pages lives.

If you're used to working on MVC apps, then the api.js file is very much the controller; the intermediary between the data (the _articles) and what the user sees (the pages).

If you understand how the API works, then the rest of the app is fairly rudimentary, so let's start by going over that.

API

The API is based on the API from this Vercel demo project.

It exports three functions needed by the various pages within the app:

getArticlesgetArticleBySlugallContainingFolders

allContainingFolders

I'll start with the simplest of these: allContainingFolders.

This function returns any folder within the _article folder, that contains a markdown article.

import fs from 'fs';

import { join } from 'path';

const articlesPath = join(process.cwd(), '_articles');

export const allContainingFolders = () =>

['', ...fs.readdirSync(articlesPath)].filter(file => file.slice(-3) !== '.md');

process.cwd() returns the current working directory. The join() function, joins the arguments you give it, as a path. So by running join(process.cwd(), '_articles'), we pass it the current working directory, followed by _articles, to give us the path to our _articles folder.

This is set to the articlesPath variable.

fs (short for 'file system') is a Node library. The readdirSync() function (short for 'read directory synchronously') returns the contents of the directory that you pass it.

So fs.readdirSync(articlesPath) returns an array of all files and folders which are direct children of the _articles folder.

Looking back to the file tree above, that is ['my-story.md', 'projects', 'templates'].

We are looking just for folders here, not files, so .filter(file => file.slice(-3) !== '.md') removes any returns where the last three characters of the string are .md (so in this example, it will remove 'my-story.md').

However, because there is a Markdown article within the _articles folder itself, we also want to return this, hence adding '' to the returned array (the my-story.md article is a permanent fixture of this app, so no need to programatically check if a Markdown file exists as a child to the _articles directory).

Therefore, given the file tree above, allContainingFolders() will return [ '', 'projects', 'templates' ].

getArticleBySlug

The next exportable function in the API is getArticleBySlug. This returns one article, based on the slug passed-into it.

A 'slug' in this context is the part of the URL that comes after the last backslash. So on this page, the slug is jethro-codes. On the https://jethro.codes/my-story page, the slug is my-story.

As a side-note, I was curious why it's called a slug, because when I think of a slug, I think of a snail without a shell, which seems completely irrelevant here.

The best explanation I could find was this StackOverflow answer, which gives a couple of possibilities for the origin of 'slug' in this context.

It's either "an informal name given to a story during the production process" of the printing press, or "screenplays had "slug lines" at the start of each scene, which basically sets the background for that scene."

Regardless of where it came from, getArticleBySlug() returns one article, based on the slug you pass it:

import fs from 'fs';

import { join } from 'path';

import matter from 'gray-matter';

const articlesPath = join(process.cwd(), '_articles');

const directoryPath = containingFolder =>

`${articlesPath}${containingFolder ? `/${containingFolder}` : ''}`;

export const getArticleBySlug = (slug, fields = [], containingFolder = '') => {

const realSlug = slug.replace(/\.md$/, '');

const fullPath = join(directoryPath(containingFolder), `${realSlug}.md`);

const fileContents = fs.readFileSync(fullPath, 'utf8');

const { data, content } = matter(fileContents);

const items = {};

fields.forEach(field => {

if (field === 'slug') {

items[field] = realSlug;

}

if (field === 'section') {

items[field] = containingFolder;

}

if (field === 'content') {

items[field] = content;

}

if (field === 'minsToRead') {

items[field] = Math.ceil(content.split(' ').length / 200);

}

if (typeof data[field] !== 'undefined') {

items[field] = data[field];

}

});

return items;

};

The getArticleBySlug function accepts three arguments:

The slug of the article, the fields within the article that you want returned (we'll get into that in a moment), and the containingFolder.

To start with, const realSlug = slug.replace(/\.md$/, ''); simply removes the .md extension, if one is passed-in on the slug, and sets the resulting string to realSlug.

For example, if I passed 'my-story.md' in as the slug argument, then 'my-story' would be set to realSlug.

On the next line, we use the join() function again (covered in the previous section).

The directoryPath() function simply checks whether a containingFolder is present. If it is, it returns a string of the articlesPath followed by the containing folder, if not it will just return the articlesPath.

So const fullPath = join(directoryPath(containingFolder), `${realSlug}.md`); sets the full path of the location of the article, to the fullPath variable.

Now that we have this path, we pass it to fs.readFileSync (read file synchronously), which returns the contents of the file path we pass to it.

So, for example, if our fullPath variable is set to jethro-codes/_articles/projects/meals-of-change.md, then const fileContents = fs.readFileSync(fullPath, 'utf8'); sets the contents of the meals-of-change.md file to the fileContents variable, in utf8 format.

Lastly we pass this fileContents to gray-matter.

What gray-matter does, is allow us to add YAML to the top of our Markdown files.

For example, at the top of this file that I'm typing right now, is the following:

---

title: 'jethro.codes'

description: 'A look behind the mechanics of how this app utilises Markdown files to automatically update the homepage and other pages.'

coverImage: '/images/projects/jethro-codes/hero-screenshot.png'

published: '2022-04-27'

tags: 'Next JS, React, Tailwind CSS, Vercel'

---

When we import matter from 'gray-matter'; and then call matter(fileContents), it returns an object with two keys: data and content.

The value of content is the Markdown that comes after this YAML code, so in this article:

I wasn’t going to write an article about this app, because I thought it’d be a bit weird to write about an app within the app. Some kind of appception...

(and this is exactly what I meant)

It contains formatting, although for simplicity I won't add that here (we'll get to it later).

The value of data is another object, which contains the "data" of this YAML code, for example:

data: {

title: 'jethro.codes',

description: 'A look behind the mechanics of how this app utilises Markdown files to automatically update the homepage and other pages.',

coverImage: '/images/projects/jethro-codes/hero-screenshot.png',

published: '2022-04-25',

tags: 'Next JS, React, Tailwind CSS, Vercel'

}

We then use object destructuring to set the data and content to data and content variables respectively:

const { data, content } = matter(fileContents);

Now we have all that we need to know about the article.

What we eventually return from getArticleBySlug is the const items = {}; object, so now it's just a case of filtering only the data that we want to return, and appending this data to items.

This is where the fields argument of getArticleBySlug comes in. To save accidentally returning too much data, we must pass-in every field we want returned.

We then loop-over each of these fields, and assign them to items accordingly:

fields.forEach(field => {

if (field === 'slug') {

items[field] = realSlug;

}

if (field === 'section') {

items[field] = containingFolder;

}

if (field === 'content') {

items[field] = content;

}

if (field === 'minsToRead') {

items[field] = Math.ceil(content.split(' ').length / 200);

}

if (typeof data[field] !== 'undefined') {

items[field] = data[field];

}

});

In the client-side code, the containingFolder is called the section, for example the projects section or the templates section.

The minsToRead field splits the content based on spaces to (roughly) give the number of words in the article (content.split(' ').length).

This number is then divided by 200, on the assumption that a person reads around 200 words per minute.

That's the more conservative end of the spectrum of reading speed (per multiple sources), but people tend to read more slowly looking at screens, and I doubt many people will be bothering to print-off these articles to read them, so it makes sense to be at that end.

if (typeof data[field] !== 'undefined') simply checks that a field exists in data before trying to return it.

And with that, we've set all the data that we need, so return items.

getArticles

The last exportable function is getArticles.

This uses a lot of the functionality that we've already been over, except that it uses it to return multiple articles.

In the name of simplicity, I'll only add the code that we haven't been over here:

const getArticleSlugs = containingFolder => {

return fs.readdirSync(directoryPath(containingFolder));

};

const allArticles = (fields = []) => {

let articlesArray = [];

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => {

if (slug.slice(-3) === '.md') {

articlesArray.push(getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

}

});

});

return articlesArray;

};

const articlesByFolder = (fields = [], folder) =>

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

export const getArticles = (fields = [], containingFolder = '') => {

let articles = containingFolder

? articlesByFolder(fields, containingFolder)

: allArticles(fields);

return articles.sort((article1, article2) => (article1.published > article2.published ? -1 : 1));

};

getArticles accepts two arguments; fields and containingFolder.

fields is used as we've seen earlier, to set which fields from each article are returned.

If omitted, the containingFolder here determines that we return all articles, as is necessary for the homepage or the sitemap, and calls the allArticles() function. If containingFolder is provided, then it will return just the articles from within that folder by calling the articlesByFolder() function:

containingFolder ? articlesByFolder(fields, containingFolder) : allArticles(fields);

Starting with articlesByFolder(), it firstly calls getArticleSlugs().

const getArticleSlugs = containingFolder => {

return fs.readdirSync(directoryPath(containingFolder));

};

getArticleSlugs() uses the fs.readdirSync() function, which we went over earlier, and returns an array of all of the slugs contained within the given folder. For example,

getArticleSlugs('projects');

returns

['jethro-codes.md', 'meals-of-change.md'];

Now that we know all of the articles that we want to return, it's simply a case of mapping over this array, calling getArticleBySlug() (gone over in the previous section) on each one, and returning the resulting array.

const articlesByFolder = (fields = [], folder) =>

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

If instead, a containingFolder is not passed to getArticles(), we then call the allArticles() function.

This function is similar, except we want to return every slug from every folder. So firstly we map over the return from allContainingFolders() (which we went over earlier).

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {});

Within this map we run another map, calling getArticleSlugs() on each folder.

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => {});

});

We only want to call getArticleBySlug() on article slugs (and not on folders), so we then run a check that slug is in fact an article, by checking that it has an .md extension.

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => {

if (slug.slice(-3) === '.md') {

}

});

});

Finally, if slug is an article, we call getArticleBySlug(), passing-in slug and the containing folder.

The return is pushed to articlesArray, which we return from this function.

const allArticles = (fields = []) => {

let articlesArray = [];

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => {

if (slug.slice(-3) === '.md') {

articlesArray.push(getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

}

});

});

return articlesArray;

};

And with that, whether or not we passed-in a containingFolder to getArticles(), we now have an array of all the articles that we want to return, set to the variable articles.

let articles = containingFolder ? articlesByFolder(fields, containingFolder) : allArticles(fields);

The last thing we do is sort the articles by the published date.

If you remember the YAML at the top of our Markdown files, we include the date that the article is published there. This is what we use to sort them, returning the most recently published first.

articles.sort((article1, article2) => (article1.published > article2.published ? -1 : 1));

And with that, our API is done.

We can use this API by calling any of the three exported functions to return either the containing folders, a single article, or an array of articles.

The completed api.rb file is therefore:

// lib/api.js

import fs from 'fs';

import { join } from 'path';

import matter from 'gray-matter';

const articlesPath = join(process.cwd(), '_articles');

const directoryPath = containingFolder =>

`${articlesPath}${containingFolder ? `/${containingFolder}` : ''}`;

export const allContainingFolders = () =>

['', ...fs.readdirSync(articlesPath)].filter(file => file.slice(-3) !== '.md');

const getArticleSlugs = containingFolder => {

return fs.readdirSync(directoryPath(containingFolder));

};

export const getArticleBySlug = (slug, fields = [], containingFolder = '') => {

const realSlug = slug.replace(/\.md$/, '');

const fullPath = join(directoryPath(containingFolder), `${realSlug}.md`);

const fileContents = fs.readFileSync(fullPath, 'utf8');

const { data, content } = matter(fileContents);

const items = {};

fields.forEach(field => {

if (field === 'slug') {

items[field] = realSlug;

}

if (field === 'section') {

items[field] = containingFolder;

}

if (field === 'content') {

items[field] = content;

}

if (field === 'minsToRead') {

items[field] = Math.ceil(content.split(' ').length / 200);

}

if (typeof data[field] !== 'undefined') {

items[field] = data[field];

}

});

return items;

};

const allArticles = (fields = []) => {

let articlesArray = [];

allContainingFolders().map(folder => {

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => {

if (slug.slice(-3) === '.md') {

articlesArray.push(getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

}

});

});

return articlesArray;

};

const articlesByFolder = (fields = [], folder) =>

getArticleSlugs(folder).map(slug => getArticleBySlug(slug, fields, folder));

export const getArticles = (fields = [], containingFolder = '') => {

let articles = containingFolder

? articlesByFolder(fields, containingFolder)

: allArticles(fields);

return articles.sort((article1, article2) => (article1.published > article2.published ? -1 : 1));

};

Updating the app

With the API done, we now need to make use of it in a way that the app automatically updates in every way we want it to, simply by adding a Markdown file. And this is where Next.js really comes into its own.

Ignoring the sitemap for now, based on the file tree that I added earlier, we need to call the API in four different places:

📦 pages

┣ 📂 [section]

┃ ┗ 📜 [slug].js

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 my-story

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📜 index.jsLet's start with the 'My story' page, because this is the simplest of the four.

My story

Being a static page, we don't even need to fetch the paths from the API. We already know the slug that we want to use is my-story.

In order to have the article available for search engines to crawl, we're going to call the API in getStaticProps. Wanting just one article returned, we call getArticleBySlug, passing-in the my-story slug, and an array of the fields that we want returned.

import { getArticleBySlug } from '../../lib/api';

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const article = getArticleBySlug('my-story', [

'title',

'description',

'published',

'content',

'minsToRead',

'coverImage',

]);

};

If you remember earlier, I said that the content return from gray-matter "contains formatting." Well this is the point that we address that.

The article variable from the above code block, would be:

{

title: 'My Story',

description: 'Why I code',

published: '2022-04-19',

content: '\n' +

'## The pre-coding years\n' +

'\n' +

"Throughout my teenage years, I'd been very into video games, so it seemed logical that when it came to choosing my subjects for sixth-form college, that computing was one of them.\n" +

'\n' +

"On the first day of this A-level computing course, aged 16, I sat in the classroom, listening to the teacher drone on in his monotone voice about topics that I didn't understand. I looked around the class, and saw myself surrounded by peers that I couldn't relate to.\n" +

'\n' +

'I felt very out of place.\n' +

'\n' +

"I had some friends who'd taken economics and business studies, and they were raving about how fun the content had been of their first class, and how charismatic their teacher was. They had genuinely enjoyed it.\n" +

'\n' + ...,

minsToRead: 87,

coverImage: '/images/my-story/litang.jpeg',

}

I won't paste all of content, but you get the idea. It's not very nice to look at. It's Markdown as we write it, but even worse.

'\n' instead of line-breaks, + signs everywhere. Probably not how we want our final article to be formatted.

If you look back to the file tree again, you'll see a markdownToHtml.js file that we haven't mentioned yet.

markdownToHtml returns the markdownToHtml function, and here is where we call that.

import { getArticleBySlug } from '../../lib/api';

import markdownToHtml from '../../lib/markdownToHtml';

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const article = getArticleBySlug('my-story', [

'title',

'description',

'published',

'content',

'minsToRead',

'coverImage',

]);

};

const content = await markdownToHtml(article.content || '');

The full markdownToHtml.js file is as follows:

// lib/markdownToHtml.js

import { remark } from 'remark';

import html from 'remark-html';

const markdownToHtml = async markdown => {

const result = await remark().use(html).process(markdown);

return result.toString();

};

export default markdownToHtml;

remark is a tool that parses and compiles Markdown. remark-html is a plugin for remark, that converts Markdown to html.

So we call remark(), tell it to use() the html plugin, and then pass the Markdown that we want converted, in this case our article, to process.

This returns a vfile. We can call .toString() on this vfile, and return our article as html.

Going back to our getStaticProps function, we now just need to return the article as props, overwriting the content key with the parsed article.

We also pass-in the article subtitle (this is used when determining the content of the <title> tag in the page header, so is consistent across all pages within a section, hence why we set it here, rather than in the YAML at the top of each Markdown file).

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const article = getArticleBySlug('my-story', [

'title',

'description',

'published',

'content',

'minsToRead',

'coverImage',

]);

const content = await markdownToHtml(article.content || '');

return {

props: {

article: {

...article,

content,

subtitle: 'Why I became a software engineer',

},

},

};

};

There is an <ArticleContainer> component that handles displaying our articles, so we pass the article as a prop to that component, and with that we have our article, fetched from the API, and visible to search engine crawlers.

The entire file is as follows:

// pages/my-story/index.js

import { getArticleBySlug } from '../../lib/api';

import markdownToHtml from '../../lib/markdownToHtml';

import ArticleContainer from '../../components/layout/main-content/article-container';

const MyStory = ({ article }) => {

return <ArticleContainer article={article} />;

};

export default MyStory;

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const article = getArticleBySlug('my-story', [

'title',

'description',

'published',

'content',

'minsToRead',

'coverImage',

]);

const content = await markdownToHtml(article.content || '');

return {

props: {

article: {

...article,

content,

subtitle: 'Why I became a software engineer',

},

},

};

};

I'm not going to go over the <ArticleContainer> component itself, or any child component in any detail, because it's pretty simple.

But just briefly, it renders an <ArticleHeader> (for example, the top of this page) and an <ArticleBody> (what you're looking at right now).

The <ArticleBody> component, which is where the article content is displayed, is as follows:

// components/layout/main-content/article-container/ArticleBody.js

const ArticleBody = props => {

return (

<section className='-mt-32 max-w-7xl mx-auto relative z-10 md:pb-6 sm:px-6 lg:px-8'>

<div className='flex justify-center py-4 px-4 lg:py-8 sm:px-6 lg:px-8 bg-white rounded-lg shadow'>

<div

className='prose max-w-full 2xl:max-w-[900px] prose-img:m-0 prose-img:rounded-md prose-img:shadow-lg prose-pre:max-w-full'

dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: props.content }}

/>

</div>

</section>

);

};

export default ArticleBody;

If the class names all look a bit funny, then you haven't tried Tailwind yet, and you're missing-out.

However, the important part of this component is dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: props.content }}. This renders the value of props.content (our article) within the containing <div> tag.

dangerouslySetInnerHTML is named as such, because if you're allowing other people to enter data that is rendered by dangerouslySetInnerHTML, you're leaving users vulnerable to Cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks.

However, as the only HTML being rendered here comes from the Markdown articles that I wrote, it's perfectly safe.

And with that, in our most simple case of displaying the 'My story' article, we are done.

[slug].js

Next let's look at [slug].js. This does exactly the same thing as my-story, with the exception that the page name is dynamic.

And what that means, is that in addition to getStaticProps, we also have to run the getStaticPaths function, in order to establish the page names.

It's worth at this point, establishing how the various sections of the app are populated.

When you look at the sidebar (or the Navbar menu if you're on mobile), and you see Home, Projects, Templates etc., how did they get there?

I like to keep related data in one place, so I have a useSectionDetails hook that contains all of these section details:

// hooks/useSectionDetails.js

import {

ChatIcon,

HomeIcon,

PaperClipIcon,

TemplateIcon,

TrendingUpIcon,

} from '@heroicons/react/outline';

const contact = 'contact';

const home = 'home';

const myStory = 'my-story';

const projects = 'projects';

const templates = 'templates';

export const sectionOrder = [home, projects, templates, myStory, contact];

export const articleSections = [projects, templates];

const useSectionDetails = () => {

const sectionDetails = sectionName => {

switch (sectionName) {

case contact:

return {

title: 'Contact',

linkText: 'Contact',

route: `/${contact}`,

icon: ChatIcon,

};

case home:

return {

title: 'jethro.codes',

description: 'My home for everything code',

linkText: 'Home',

route: '/',

icon: HomeIcon,

};

case myStory:

return {

title: 'My Story',

linkText: 'My Story',

route: `/${myStory}`,

icon: TrendingUpIcon,

};

case projects:

return {

title: 'Projects',

description: 'Going in depth on my latest personal projects',

linkText: 'Projects',

route: `/${projects}`,

icon: PaperClipIcon,

};

case templates:

return {

title: 'Templates',

description: 'Project templates to save time starting from scratch',

linkText: 'Templates',

route: `/${templates}`,

icon: TemplateIcon,

};

default:

throw new Error(`Unrecognised section name '${sectionName}' passed to useSectionDetails`);

}

};

return sectionDetails;

};

export default useSectionDetails;

I won't go over every case of how this data is used, because most of it is irrelevant to the Markdown articles, and that's what I want to focus on here. However, there is one important line:

export const articleSections = [projects, templates];

This articleSections variable sets which sections of our app contain articles.

At the time of writing, that's just projects and templates, but in the future (if I find the time), may include blog, packages, gems, tutorials etc.

Going back to our getStaticPaths function in [slug].js, we import articleSections to know where we need to look for articles.

import { getArticles } from '../../lib/api';

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

const articles = [];

articleSections.map(section => {

articles.push(getArticles(['slug', 'section'], section));

});

};

If you remember the getArticles function from earlier, it returns all the articles for a given section.

However, as we're mapping over all sections, the articles array will contain all articles (with the exception of 'my-story', as that's not contained within a section).

At this stage, as we're only establishing the paths of these articles, we're only interested in returning the slug and the section.

So with all articles now set to articles, we can loop over them, and set the section and the slug.

📦 pages

┣ 📂 [section]

┃ ┗ 📜 [slug].jsSo our full getStaticPaths function becomes:

import { getArticles } from '../../lib/api';

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

const articles = [];

articleSections.map(section => {

articles.push(getArticles(['slug', 'section'], section));

});

return {

paths: articles.flat().map(article => {

return {

params: {

section: article.section,

slug: article.slug,

},

};

}),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

};

The rest of the [slug].js file is fairly similar to the 'My story' section, as now having each of the article paths, we just need to fetch each article from the API.

getStaticProps will run for every article, passing-in the params that we returned above.

return {

params: {

section: article.section,

slug: article.slug,

},

};

So when we call getStaticProps, we already have the slug and the section. We can therefore call getArticleBySlug(), and subsequently markdownToHtml() exactly as we did in the 'My story' section:

import { getArticleBySlug } from '../../lib/api';

import markdownToHtml from '../../lib/markdownToHtml';

export const getStaticProps = async ({ params }) => {

const article = getArticleBySlug(

params.slug,

['title', 'description', 'published', 'content', 'coverImage', 'tags', 'minsToRead'],

params.section

);

};

The only slight additions, is that the subtitle will change, depending on the section, so we have a simple function for that, where we pass-in params.section as the argument.

const subtitle = section => {

switch (section) {

case 'projects':

return 'Anatomy of a Project';

case 'templates':

return 'Project Template';

default:

return '';

}

};

And we also need to determine the type.

If you go to the very top of this page, you'll see PROJECT in blue letters, right above the title.

That's the type, as in the type of article. And for all current sections, and future sections that I've so far conceived (ignore blog), simply removing the last 's' from the section name determines the type (so projects becomes PROJECT, templates becomes TEMPLATE etc.).

For as long as that remains true, then params.section.slice(0, -1) will suffice.

Every other part of the [slug].js file was covered in the 'My story' section.

The full [slug].js file is therefore:

// pages/[section]/[slug].js

import { getArticleBySlug, getArticles } from '../../lib/api';

import markdownToHtml from '../../lib/markdownToHtml';

import ArticleContainer from '../../components/layout/main-content/article-container';

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

const Article = ({ article }) => {

return <ArticleContainer article={article} />;

};

export default Article;

export const getStaticProps = async ({ params }) => {

const article = getArticleBySlug(

params.slug,

['title', 'description', 'published', 'content', 'coverImage', 'tags', 'minsToRead'],

params.section

);

const content = await markdownToHtml(article.content || '');

const subtitle = section => {

switch (section) {

case 'projects':

return 'Anatomy of a Project';

case 'templates':

return 'Project Template';

default:

return '';

}

};

return {

props: {

article: {

...article,

content,

type: params.section.slice(0, -1),

subtitle: subtitle(params.section),

},

},

};

};

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

const articles = [];

articleSections.map(section => {

articles.push(getArticles(['slug', 'section'], section));

});

return {

paths: articles.flat().map(article => {

return {

params: {

section: article.section,

slug: article.slug,

},

};

}),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

};

[section]/index.js

So far what we've been able to achieve, is dynamically fetching and displaying the articles, simply by adding a Markdown file.

getStaticPaths in [slug].js will check for any articles that exist at build time.

However, at this stage although the articles will be hosted within the app, no one will have any way of finding them or knowing that they're there, because so far we haven't updated the homepage or the section page. So let's take care of that next.

📦 pages

┣ 📂 [section]

┃ ┗ 📜 [slug].js

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 my-story

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📜 index.jsLike [slug].js, [section]/index.js is a dynamic file where we have to tell it its name by using getStaticPaths.

Luckily, we already know the various sections of our app, because they're contained within the articleSections variable or our useSectionDetails hook. So just like in [slug].js, we import that variable.

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

Within getStaticPaths we again map over this array, although this time we don't care about fetching any slugs; we simply want to tell [section]/index.js which paths to create.

Assuming that articleSections returns ['projects', 'templates'], then we want a projects page and a templates page, so our getStaticPaths function becomes:

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

return {

paths: articleSections.map(section => {

return {

params: {

section: section,

},

};

}),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

};

On these 'section' pages, we have no interest in displaying the entire article, we simply want enough information to populate the cards on each page, and to link to the article itself.

To that end, we need five pieces of information about each article: title, description, slug, coverImage and section.

So in getStaticProps, we call our API getArticles function, pass-in the section (projects or templates) for whichever page we're on, as well as the required fields, and set the returned array to the allArticles variable. We then return allArticles as our props.

import { getArticles } from '../../lib/api';

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

export const getStaticProps = async ({ params }) => {

const allArticles = getArticles(

['title', 'description', 'slug', 'coverImage', 'section'],

params.section

);

return {

props: { allArticles },

};

};

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

return {

paths: articleSections.map(section => {

return {

params: {

section: section,

},

};

}),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

};

From here, we have three main components that make-up this page; the <SectionHome> component, a <HorizontalCardsContainer> and a <HorizontalCard>.

// pages/[section]/index.js

import { getArticles } from '../../lib/api';

import HorizontalCard from '../../components/ui/HorizontalCard';

import HorizontalCardsContainer from '../../components/ui/HorizontalCardsContainer';

import SectionHome from '../../components/layout/main-content/section-home';

import { articleSections } from '../../hooks/useSectionDetails';

import useHeroImage from '../../hooks/useHeroImage';

const Section = ({ allArticles }) => {

return (

<SectionHome heroImage={useHeroImage(allArticles)}>

<HorizontalCardsContainer>

{allArticles.map(article => (

<HorizontalCard key={`${article.title}-card`} cardDetails={article} />

))}

</HorizontalCardsContainer>

</SectionHome>

);

};

export default Section;

export const getStaticProps = async ({ params }) => {

const allArticles = getArticles(

['title', 'description', 'slug', 'coverImage', 'section'],

params.section

);

return {

props: { allArticles },

};

};

export const getStaticPaths = () => {

return {

paths: articleSections.map(section => {

return {

params: {

section: section,

},

};

}),

fallback: 'blocking',

};

};

As with other sections, I don't intend to go over the styling of these three components, as there's nothing very complex in there.

For simplicity, I've also omitted part of the [section]/index.js (mainly related to adding the <Head>).

The full file can be found here.

And with that, at build time our [section]/index.js page will create a page for each section stored within our articleSections variable, and will fetch all of the articles for that section, creating a card for each article.

That means that, just by adding a Markdown article within the correct sub-folder of our _articles folder, the article will be automatically fetched and made available to our readers.

📦 _articles

┣ 📂 projects

┃ ┣ 📜 jethro-codes.md

┃ ┗ 📜 meals-of-change.md

┣ 📂 templates

┃ ┗ 📜 rails-api.md

┗ 📜 my-story.mdHomepage

The last place that we want to display our new article is the homepage. If you were to take a look at the homepage now, you'll see that it displays the six most recently published articles.

At this point, we've done all the hard work and updating the homepage is comparatively simple.

It's not a dynamic page, so we don't need to use getStaticPaths. And as it's not a section, we don't even have to pass a containing folder to the API.

Instead, in our getStaticProps function, we want to return all articles from the API.

import { getArticles } from '../lib/api';

getArticles(['title', 'description', 'slug', 'coverImage', 'section', 'published', 'minsToRead']);

As they are returned from the API already sorted by the most recently published, we simply need to keep the first six of them, and can do that with slice.

import { getArticles } from '../lib/api';

getArticles([

'title',

'description',

'slug',

'coverImage',

'section',

'published',

'minsToRead',

]).slice(0, 6);

We can set these six articles to the variable featureArticles, and return that as props from getStaticProps.

import { getArticles } from '../lib/api';

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const featureArticles = getArticles([

'title',

'description',

'slug',

'coverImage',

'section',

'published',

'minsToRead',

]).slice(0, 6);

return {

props: { featureArticles },

};

};

From here, this page works very much like [section]/index.js, with the exception that we use vertical cards, instead of horizontal cards.

So again omitting some irrelevant code (like the <Head> section), our full homepage (index.js) file becomes:

// pages/index.js

import SectionHome from '../components/layout/main-content/section-home';

import VerticalCard from '../components/ui/VerticalCard';

import VerticalCardsContainer from '../components/ui/VerticalCardsContainer';

import { getArticles } from '../lib/api';

import useHeroImage from '../hooks/useHeroImage';

const Home = ({ featureArticles }) => {

return (

<SectionHome heroImage={useHeroImage(featureArticles)}>

<VerticalCardsContainer title='Latest content'>

{featureArticles.map(article => (

<VerticalCard key={`${article.title}-card`} cardDetails={article} />

))}

</VerticalCardsContainer>

</SectionHome>

);

};

export default Home;

export const getStaticProps = async () => {

const featureArticles = getArticles([

'title',

'description',

'slug',

'coverImage',

'section',

'published',

'minsToRead',

]).slice(0, 6);

return {

props: { featureArticles },

};

};

The full homepage file can be found here.

As with other pages, our homepage will update at build time, so now by simply adding a new Markdown file, our new article is hosted (by [slug].js) and will have a card linking to it on both the section page, and the homepage.

All that's left therefore, is to update our sitemap so that search engines know that the article is there.

Updating the sitemap

📦 _articles

┣ 📂 projects

┃ ┣ 📜 jethro-codes.md

┃ ┗ 📜 meals-of-change.md

┣ 📂 templates

┃ ┗ 📜 rails-api.md

┗ 📜 my-story.md

📦 lib

┣ 📜 api.js

┗ 📜 markdownToHtml.js

📦 pages

┣ 📂 [section]

┃ ┗ 📜 [slug].js

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 contact

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📂 my-story

┃ ┗ 📜 index.js

┣ 📜 _app.js

┣ 📜 index.js

┗ 📜 sitemap.xml.jsThis is the file tree that I showed you back at the beginning of this article. And the last part that we need to cover is the sitemap.xml.js file at the bottom.

sitemap.xml.js is a component within which we don't render anything. Instead we're going to use its getServerSideProps function, which is called once the URL (in this case jethro.codes/sitemap.xml) is hit.

getServerSideProps has a res object (short for 'response'), and we're going to override this response with our sitemap.

const Sitemap = () => {};

export default Sitemap;

export const getServerSideProps = ({ res }) => {

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/xml');

res.write(sitemap);

res.end();

return {

props: {},

};

};

At this point, the sitemap variable (within res.write(sitemap)) doesn't exist; we'll get to that in a second.

I just want to try and make clearer exactly what we're doing.

When calling getServerSideProps, we get a res (response) object.

We then set the header of this response to have a content-type of xml. We then write our sitemap to the body of this response, before we end the response (sending it back to the original request).

The return statement here does nothing; it's simply a requirement of getServerSideProps, so we include it so as to not throw an error.

With that done, we now need to populate the sitemap variable with our sitemap.

sitemap is going to be a string, and within it we will interpolate the URLs for the various pages of our app. So to start, sitemap will be a template literal with the structure of our xml file.

const sitemap = `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<urlset xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9">

</urlset>

`;

Within the <urlset> tags, we want to have our URLs.

Sitemaps will often contain <lastmod> (last modified), <changefreq> (change frequency) and <priority> tags. For simplicity, I've omitted them. My only concern with a sitemap is making Google (and other search engines) aware that a page exists. So the only tag I want to use for each page is <loc> (location).

To start with, we need to know the base URL of the app.

export const getServerSideProps = ({ req }) => {

const baseUrl = `${process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production' ? 'https://' : 'http://'}${

req.headers.host

}`;

};

To start with we check whether we're in production or not, and return 'https://' if we are.

This step isn't really necessary, as a search engine is only ever going to find the production version of a sitemap, so we could just hardcode 'https://'. However, when working in development, it's good to see that the correct URL is being generated.

Next we call req.headers.host.

req is the request, and within the headers object, we have the host. Locally the host is 'localhost:3000', in production it's 'jethro.codes'.

We interpolate these two strings together to set the baseUrl variable.

So in production, baseUrl will be set to https://jethro.codes.

Next we want to fetch all the articles that we have in the app. We do this by calling the getArticles() function in our API.

We want all articles, so we don't pass-in a containing folder, and as we're only interested in determining the location of these articles, only request the slug and section fields.

import { getArticles } from '../lib/api';

const allArticles = getArticles(['slug', 'section']);

The allArticles variable will therefore be something like:

[

{ slug: 'my-story', section: '' },

{ slug: 'jethro-codes', section: 'projects' },

{ slug: 'meals-of-change', section: 'projects' },

{ slug: 'rails-api', section: 'templates' },

];

We want to get the relative path to each article, and having the slug and the section, we can easily do that:

const allArticlePaths = allArticles.map(

article => `${article.section && `${article.section}/`}${article.slug}`

);

Here we map over allArticles, and if a section is present, we interpolate the section with the slug. If no section is present, we just return the slug. Our allArticlePaths variable will therefore be:

['my-story', 'projects/jethro-codes', 'projects/meals-of-change', 'templates/rails-api'];

These are the relative paths to all of our articles, however we still need the paths to the other pages of our app.

You may have noticed one oversight at this point.

Earlier in our API, we had the following code:

export const allContainingFolders = () =>

['', ...fs.readdirSync(articlesPath)].filter(file => file.slice(-3) !== '.md');

We exported this function, yet we never actually used it anywhere outside of our API.

Here is where we finally get to use it.

If you remember back to the allContainingFolders section of this article, this function returns any folder within _article that contains a Markdown article, so here it will be:

['', 'projects', 'templates'];

That's the homepage, the projects page, and the templates page.

We have all our articles set to the allArticlePaths variable, and the homepage and section pages accessible by importing the allContainingFolders function.

That covers all the pages of our app... apart from one.

The one outlier in our app is the contact page. This is the only page that has absolutely nothing to do with any articles.

And although there was a part of me tempted to add the functionality to find this page programatically, as it is, and probably always will be the only page that isn't present in allArticlePaths or allContainingFolders, finding it programatically, the juice isn't really worth the squeeze.

So to get the paths to all the pages of this app, we can just do:

const allPaths = [...allContainingFolders(), 'contact', ...allArticlePaths];

Now that we have the paths to every page in our app, all we need to do is map over them and add them to our sitemap variable.

They need to be contained within <url><loc> tags, and we want to append the path onto the baseUrl that we established earlier, so our sitemap variable can be set as follows:

const sitemap = `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<urlset xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9">

${allPaths.map(path => `<url><loc>${baseUrl}/${path}</loc></url>`).join('')}

</urlset>

`;

And that's all we have to do.

Our full sitemap.xml.js file therefore becomes:

// pages/sitemap.xml.js

import { allContainingFolders, getArticles } from '../lib/api';

const Sitemap = () => {};

export default Sitemap;

export const getServerSideProps = ({ req, res }) => {

const baseUrl = `${process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production' ? 'https://' : 'http://'}${

req.headers.host

}`;

const allArticles = getArticles(['slug', 'section']);

const allArticlePaths = allArticles.map(

article => `${article.section && `${article.section}/`}${article.slug}`

);

const allPaths = [...allContainingFolders(), 'contact', ...allArticlePaths];

const sitemap = `<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<urlset xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9">

${allPaths.map(path => `<url><loc>${baseUrl}/${path}</loc></url>`).join('')}

</urlset>

`;

res.setHeader('Content-Type', 'text/xml');

res.write(sitemap);

res.end();

return {

props: {},

};

};

To see the page that we generated here, go to jethro.codes/sitemap.xml.

Wrap-up

By automatically updating the sitemap, we've successfully got our app working so that by simply adding a new Markdown article, the article gets hosted, the homepage and the section page get updated, and the sitemap updates to let Google and other search engines know that our article is there.

If you've made it this far, then I hope that everything I've been over is clear... or at least clear enough for you to start hacking away yourself.

If anything wasn't clear, or if there's anything else in this app that you think should be covered in this article, let me know in an email.

Otherwise, happy hacking!

Useful links

- jethro.codes GitHub repo - https://github.com/jro31/jethro-codes